Yesterday I went along to the RSBP’s Central London Local Group. They meet in the Scottish church hall behind Harrods in Knightsbridge: on the short walk from the tube I passed some amazingly expensive-looking people, associated with a lot of taxis and a green-coated commissionaire. Inside, I nibbled a biscuit and was offered a raffle ticket.

The group’s AGM was billed to last 30 minutes: it did, and was presented efficiently and interestingly by the members of the organizing committee. They regularly run 10 coach trips each year to out-of-town reserves as far away as Lymington and Slimbridge. They hold a similar number of indoor meetings, with at least one scientific talk, a non-birding talk, one on a specific bird, and some on good birding places in Britain or overseas. Audiences are increasing; the group is more than breaking even, and makes an annual donation to RSPB projects.

The main talk was by Ian Dillon who manages the RSPB’s Hope Farm in Cambridgeshire. It’s not exactly a nature reserve: it’s a working farm, bought after a successful fundraising campaign in 1999, and run “for Food, Profit and Wildlife”. Dillon used to be warden of a nature reserve up in Orkney caring for Corncrakes, once a familiar farmland bird (I actually remember our music master at school berating the congregation during a singing practice for sounding like Corncrakes (they go Crek, Crek not terribly musically), which tells you how long ago it was) but now almost extinct except in the Outer Hebrides where the shy birds don’t have to try to outrun giant modern tractors that can harvest a field at 25mph.

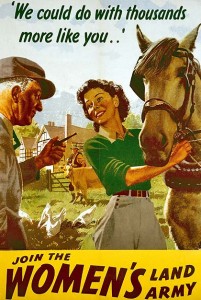

Dillon gave a practised and lively talk about Hope Farm, covering the 90% decline in some farmland birds since 1970 (Grey Partridge, Corn Bunting, Turtle Dove among them) as farmers have, from their point of view, improved their farming. They grow twice as much wheat per hectare, up to around 8 tons. They have achieved this through intensification, using pesticides, fertilisers, mechanisation and drainage. The result is clean, healthy crops, free of weeds, pests, and diseases: but also largely free of wildlife. Specific issues for birds are the increase in winter wheat and barley, meaning there is no food-rich stubble for them to feed on in the winter, and the 1960s policy of grubbing out hedges to increase field size and hence efficiency, removing nesting sites, insects, and roosts. The speed of modern farm machinery is also fatal to wildlife such as Grey Partridges and hedgehogs. The overall effect is an average 50% decline in farmland birds since 1970; it has not quite run to completion, with numbers continuing to decline slowly in what is in the more arable parts of Britain such as East Anglia effectively a sterile countryside adapted to industrial food production.

Hope Farm runs a conventional wheat-oilseed rape – wheat – beans/peas rotation. With the EU farm subsidy, and farmed by an efficient large contractor – each big machine only visits the farm for a few days per year: it would be silly for Hope Farm to buy its own – the farm makes a profit and achieves good yields, so in theory farmers should be happy to listen to what the farm has to say about its practices, however much of a turn-off they find the name ‘RSPB’.

For as well as farming, Hope Farm aims to increase wildlife, at least its farmland birds. It has been successful so far: since 2000 the number of Skylark territories has increased fourfold, while Yellowhammers have recovered to more than their 1960s levels – luckily an early BTO survey covered the farm. Wintering bird numbers are well up, too – 200 Yellowhammers, 37 Grey Partridges, 172 Skylarks, exceeding expectations. This has been achieved with two main changes: some small inconvenient-to-plough areas have been sown with mixed crop seeds so different birds each get winter food; and five metre square patches, dotted around the arable fields, have been left bare, enabling Skylarks to feed in summertime. Curiously the Skylarks actually continue to nest in the dense crops (of wheat, etc), but once these become tall they find it hard to land there, so without bare patches they tend to nest close to the ‘tramlines’ made by the tractor when spraying. The nests don’t get run over, nor are the birds destroyed by harvesting (they’ve flown by then), but nesting near the tramlines so they can readily take off and land makes them vulnerable to passing predators – foxes, badgers, hedgehogs – all of which use the tramlines. Very careful survey work, with remote cameras, proved that this was the problem. So the lark patches help, but in rather an indirect and surprising way.

Hope Farm has to date been less successful at persuading farmers to follow suit. The RSPB set out confident that with solid evidence of effectiveness and profit, the world would do what they said. Ah, they reckoned without the slow, cautious, individualistic, calculating ways of the farmer. After all, why do anything that doesn’t pay? One answer is that it does: you qualify for an agro-environment scheme, which increases your subsidy. Another is, that trying to farm those small awkward corners doesn’t pay, either: you spend more time and money trying to work those bits of land, which slope, or are shaded, or have poor drainage, or are more susceptible to disease, and the effort, diesel, seed, pesticides and fertiliser you use are not justified by the small extra returns. This is for the farmer a practical matter; for us and the RSPB and our children, a matter of whether there will be wildlife in farmland, or not.

The evening ended with a delicious finger buffet and a glass of Cava. The group is active, enthusiastic, and runs a varied programme. I shall go along. Why don’t you?