London Wildlife Trust’s ecologist, Alex, has set about finding out what is actually happening to multiple sorts of wildlife across the Trust’s many reserves, including quite a few that don’t have a warden, or even a group of volunteers. This is quite the task, when you consider that each reserve may contain multiple habitats — woodland, meadow, and pond, for instance — and that each habitat may be monitored for different sorts of beastie, like amphibians or pond invertebrates, and that each site may be sampled in each of several places (different ponds), each with multiple micro-habitats (open water, between plants, …), and each sampled repeatedly through the season.

Alex has set up templates for each type of monitoring in the Memento Database app, which has the merit of being free to download, and of being usable entirely offline if people are saving their mobile’s battery or have a wobbly data connection. We downloaded the app and installed her ‘Aquatic invertebrates’ template.

Then we half-filled a plastic tray with pond water and told the template to create a new sample record. We put in our initials, agreed a numbering for our four ponds: the seasonal ponds P1, P2, P3, and the main one P4, and filled in the amount of shade on the water, amount of vegetation, depth of water (the net handle came in handy here as a depth gauge) whether there was rubbish or dead wood or signs of eutrophication or a few other parameters, and then looked VERY carefully at the “water” in the tray to see if there were any beasties in there BEFORE we’d collected our carefully-taken sample. So if you find 5 Daphnia water-fleas in there, you have to subtract that number from your sample when you count it…

One of us — Andy or me — then took the net, swished it about in the chosen area of the pond for 3 seconds, and brought the sample to the tray, carefully washing the net in the tray water.

The template had been constructed for Android. Andy had an interesting time working out how to use it on his i-phone. On my Android phone, it turned out to be a good deal simpler to use, though with three tabs to complete, each with a long list of fields of various sorts, and a nearly invisible SAVE button (the critical bit, really), it took a little practice to get used to it.

The other requisite skill, of course, was being able to see and recognize the little beasties in the water. I thought I’d have no difficulty as I know my Midge larvae from my Mayfly nymphs: but a large number of the pondy bestioles (all technical terms here) turned out to be extra-small water fleas too small to make out clearly without reading glasses (at home, naturally), and too deep in the water to focus on with my hand-lens. So for next time, glasses, and my oversized Sherlock Holmes magnifying glass that someone gave me when I was a teenager — absurdly low magnification, but a wide field of view and a large depth of field. Aha.

The smidgeon-sized millibeasts on which the survey depended (at least on this lovely April afternoon) were the tiniest Daphnia I’d ever seen; equally tiny Cyclops; and (if possible) even smaller Water Mites. My first reaction was, we’ll never manage to ID those things, let alone count them. But you know what? It’s possible, even with a bit of presbyopia. How? Well, the trick is to rely on the “jizz”, the plane-spotter’s “general impression, size and shape” (yes, that must have been “giss” originally, but pronounced jizz anyway), i.e. how it moves, what sort of smudge of colour you can make out, and any hints as to what shape the thing would have if you were actually able to pop it into a watchglass and peer at it properly with a binocular microscope (at home, advisedly).

Daphnia are basically oval, and have a slight reddish hue to them. Cyclops are slender, tapering to a point at the tail, and look greyish. If you’re really lucky, you get a female Cyclops with a pair of obvious egg-sacs either side of her tail.

So you can tell Daphnia and Cyclops apart even if you can barely make them out, because they give a different impression. And, Daphnia swim on their sides, thrashing along with their feathery antennae; while Cyclops swim on their bellies, flicking their antennae like an athlete doing butterfly-stroke with their arms. Both therefore move in little jumps or saccades. The other micro-bestiole that we had in numbers today was the Water Mite. They’ve got 8 legs and a basically round body (the head does not protrude). They swim with their little legs, rather smoothly and continuously … so they don’t look anything like water-fleas except in size.

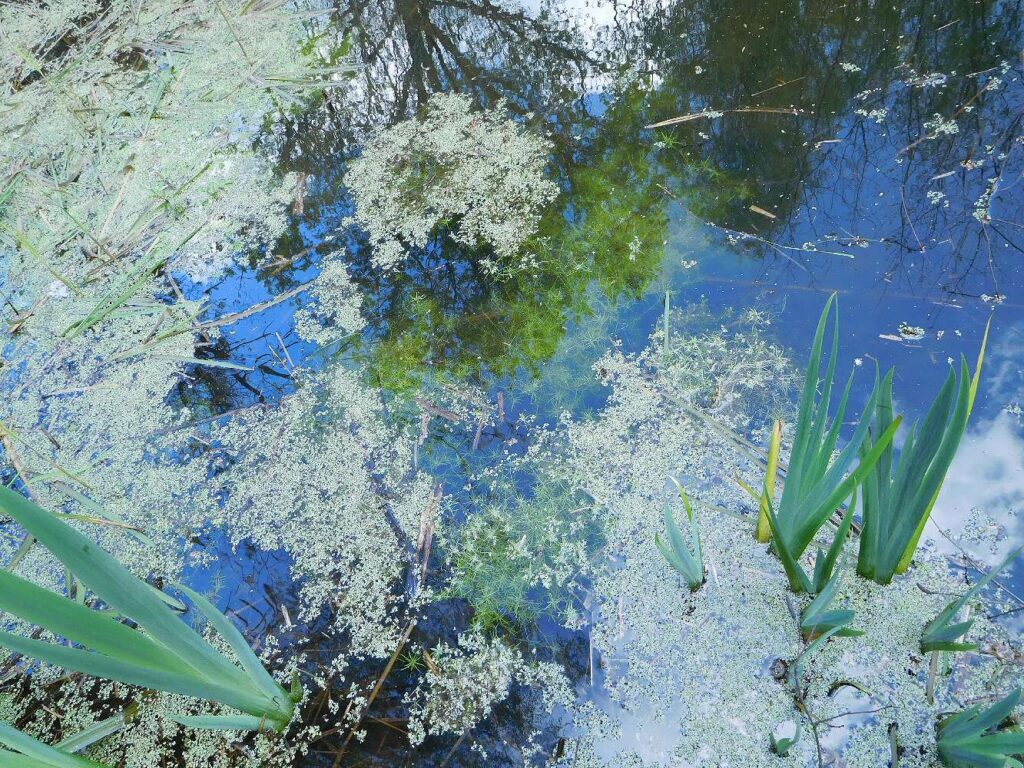

So we counted the animals in each sample. Coming to the main pond was a pleasure, as it’s a beautiful spot; the sun was warm; and the first thing we saw (rising to the surface of the pond) was a nice big male newt, the first of the year. More, Alex identified it as a breeding Male Palmate Newt, not our usual Smooth Newt: its tail goes down to a point, making it seem relatively short, and its hind feet are webbed.

I added it to the “Notes” field (this was a record of invertebrates). Andy and I found that we were getting used to the template, and filled it in a lot more quickly than our first efforts. I saved and exported the sample record to a .CSV data file, and pressed the email button. To my astonishment I only had to make a couple more clicks and the whole dataset sent itself off to Alex for analysis.

Amy Liptrot goes to live in London to escape the cramped life as a teenager on Orkney, a group of windswept islands off the north of Scotland. Her father was sectioned under the mental health act the day she left. At least she was free of the constant pressure from her happy-clappy Christian mother. In London, she parties, she drinks, she smokes, she takes drugs, she has sex. Is she happy? No. She drinks more and more, she loses one job, then another, then her boyfriend and her flat.

Something needs to be done. She’s not sure if she can stick with Alcoholics Anonymous’s talk of God, is that her mother all over again, but she tries it anyway and goes sober, along with the drug addicts and no-hopers:

“I had never injected drugs, been a prostitute, smoked crack in front of my baby, spent eight years in a Russian prison, mugged an old man in the park, or been through six detoxes and four rehabs, painfully relapsing each time. My family still spoke to me, and I had not turned yellow.”

She goes back to Orkney, still sober. A woman tells her she’s washed up: painful because not entirely untrue: but she’s on the mend. Her father’s farm had a small neat area of little fields near the farmhouse, and a big wild area where the sheep could graze, the outrun. Perhaps Amy had been away on her own outrun for those ten troubled years in London.

She stays with her mother for a bit in Orkney’s little capital town, Kirkwall. It rains for 54 days in a row in the winter; then at last some “dreamy sunsets reflected on calm sea”. She goes back to the farm and spends days building drystone dykes, thick heavy double-walls of stone. She rebuilds herself at the same time…

Greatly daring, and knowing nothing about ornithology, she applies to the RSPB to spend the summer mapping the distribution of all the breeding Corncrakes on the Orkney Islands. She gets the job. She spends the summer staying up all night, driving about and stopping the car to listen for the extraordinary “crex crex” croaking noise that gives the bird its Latin name.

She maps 31 of the elusive birds dotted about: one island has exactly one male bird. She sees a Corncrake exactly once in the entire period. Once, she arrives at a stone circle at dawn: nobody is about. She takes off her clothes and runs around it.

She discovers that the RSBP’s house on the island of Papa Westray is used to warden the bird reserve there only in summer. She asks if she can stay there in the winter. It’s not insulated, normally left empty then. She gets it: the rent is very low: “I decide that I will spend my time in the kitchen with the fire, leaving the rest of the house to the cold.” It’d be a perfect place to drink… nobody would know… but she stays sober. “There are no flatmates or close neighbours to hear me crying at night.” She recollects in tranquillity how she was sexually assaulted in London: she fought the man off, he was imprisoned; and how she crashed her car and was banned for drunk driving. She notices each day the

“moment, looking back, facing into the northerly wind … when my heart soars. I see starlings flocking, hundreds of individual birds forming and re-forming shapes in liquid geometry, outwitting predators and following each other to find a place to roost for the night. The wind blows me from behind so strongly I’m running and laughing.”

Her nephew was born soon after she went sober. “He will never see me drunk.”

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

For many years, we – London Wildlife Trust and its volunteers – have mainly tried to keep Gunnersbury Triangle open and usable: the paths not blocked by fallen trees or too tightly hemmed in by encroaching brambles, edged variously with low fences, deadhedges, a ditch or two. lines of loggery posts to nudge people to stay on the path while giving the stag beetle larvae a bit of habitat, or failing all else just long heavy logs laid on the ground end to end.

Apart from that, we’ve done what we can to stop the meadows vanishing under bramble, repaired or replaced benches and boardwalks, and left the rest of the reserve more or less to its own devices.

That has meant that much of the reserve has been heavily wooded, with a rather dense canopy, a shaded woodland floor, and a mass of ivy and bramble that has got pretty much everywhere. That’s a class 3 or degraded woodland, where the ideal is a pretty and species-diverse floral ground cover – a bluebell wood, say, or dog’s mercury, or any of the flowers adapted to pop up in spring before the deciduous trees that form the canopy come into leaf and cut out the light to the smaller plants beneath them.

Well, at last we’ve started to have a go at habitat restoration. The areas most suitable for the effort are those where the tree canopy is thinnest, so forest floor herbs have a decent amount of light throughout the summer. The north bank is clearly an ideal choice here, as it’s south-facing and in many places relatively open; it’s also less likely to be trodden down because of its steepness. If it has a disadvantage it may be that it’s very free-draining, and may get dry quickly in a hot summer.

Be that as it may, we’ve now spent a couple of sessions digging out brambles, clearing dead wood, and pulling the ivy from the ground. A heavy metal rake makes quick if tiring work of removing the ivy. With all the rain we’ve had recently, all but the biggest brambles come out satisfyingly and permanently by the roots when pulled, which they certainly don’t in a dry period.

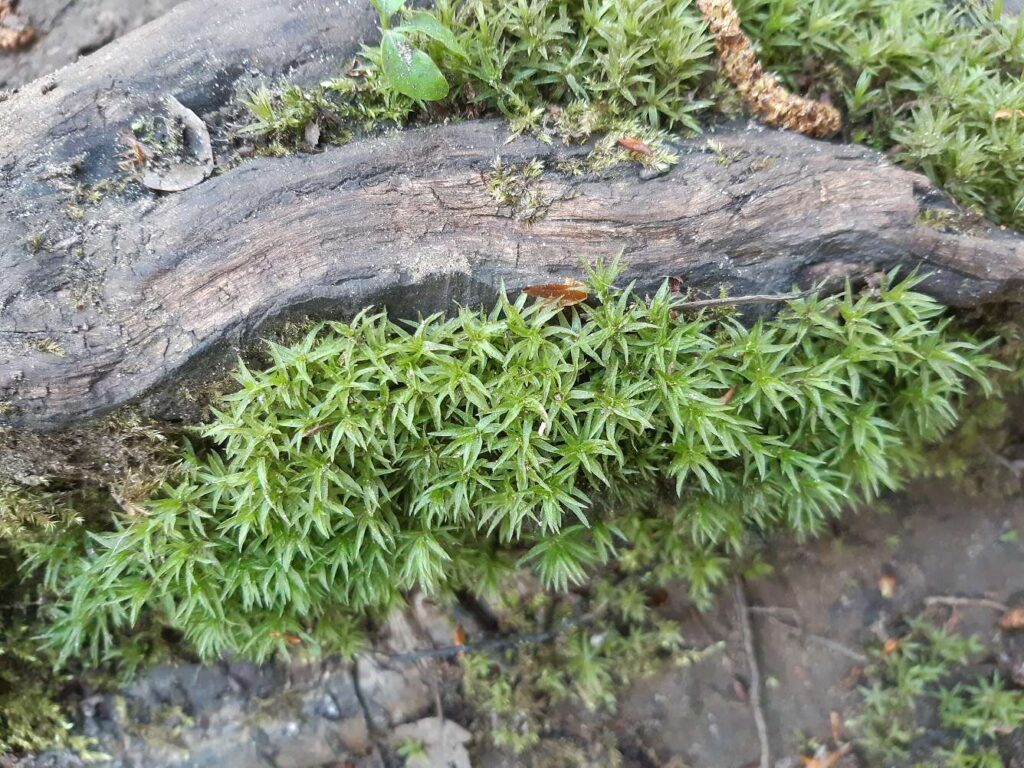

In the photo above, you can see an uncleared bit of woodland floor on the right, and a cleared area on the left. We managed to clear a 30-foot length of the north bank in one session today. Maybe we’ll get all the way up to the rather fine bluebell patch next time.

You and I have read plenty of nature books that wax lyrical about the beauty of the liminal, the unfathomable gritty reality of walking along a muddy track on the outside of town between the sewage treatment plant, the football stadium, and the business park, and suddenly being transfixed etc etc by the unearthly and astonishingly loud song (for such a tiny bird) of the wren, rising etc etc above the mundane roar of the traffic and the air conditioning fans to transport the lonely naturalist into the unparalleled ecstasy of the mundane.

Fortunately, Two Lights is nothing like that.

James Roberts is an artist as well as a poet. He is lucky enough to live in the quiet countryside of the Welsh Borders: and to enjoy some of the country’s darkest skies, so that he can see thousands of stars, the milky way and comets. And he writes about it simply and beautifully. But no, he does more. He lets his imagination, his atlas of the world, the journeys he made when he was young, what he has read, his father’s decline and death from Parkinson’s, his wife’s journey through breast cancer and radiotherapy, history, the loss of wild places everywhere, take him to different places, and express what everyone is feeling in these crazy times, love and loss and desperation and, yes, beauty despite it all.

Roberts is an experienced artist, with the gift to describe his subject plainly without either getting excessively technical, or talking down to his readers: “Most artists are obsessed with space. Positive space is the area of a picture which contains the subject, the details, the face or figure in a portrait, the arranged objects in a still life, the trees and rocks in a landscape. Negative space is the area of the picture which surrounds the subject.”

He goes at once to the heart of the matter: “I’ve spent hours staring at Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, wondering how he managed to achieve the milky light in the room, the sense of silence, the open-mouthed expression on the pregnant woman’s face and the depths behind it.”

I don’t know about you, but I immediately downloaded an image of the painting – the book’s illustrations are all of Roberts’s own work – and spent several minutes with my new-found knowledge of positive and negative space, wondering how Vermeer had done it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy. Then I wondered how Roberts had written about it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy.

Two Lights begins with a chapter on the dawn, and ends with one on dusk, presumably the two lights of the title. Roberts says he is attracted to these times, these transitional lights, when forms appear or dissolve, when shapes shift, when negative space appears positive or vice versa, when birds sing, when what seems solid and permanent is revealed as constantly changing.

The book’s subtitle, Walking through Landscapes of Loss and Life, speaks of its themes: personal connection to a landscape and its wildlife, to all of nature; and within that, a connection between personal loss and the silent, invisible shockwave of human impact on all of nature, from the paleolithic to the present.

You might think that with global warming, deforestation, overfishing, soil erosion, draining of wetlands, damming of rivers, pesticides, pollution, growth of cities, nights so bright with streetlights that citydwellers never see more than half-a-dozen stars, nights without nightingales, corn without cornflowers, meadows without meadowsweet, hedges without “immemorial elms”, roadsides without primroses, garden Buddleia bushes without butterflies, the extinction of species… that we would need no reminding that we have lost something.

But Roberts is right, we’ve forgotten. Our leaders think of wars and armies, of immigrants and policies, of votes and elections, ignoring what is happening to the world all around them: like officers fighting on the bridge of a sinking ship.

He’s also right that lecturing doesn’t work. Perhaps the oblique, feather-light, razor-sharp insight of an artist and poet may do better.

Roberts walks the bare hills and valleys of Wales, recalling “the forest of my imagination … hiding beneath my feet, in these hills, waiting to regrow.” The trees were cleared thousands of years ago, the first people of Britain burning gaps in the forest to make way for their fields. Now:

“News bulletins have been covering fires in Greece and Italy, and also those in California … on the map, the brightest areas are in Africa. The whole of the Congo seems to be burning, Central and East Africa lit up, Zambia, Angola, Tanzania, Kenya. There are fires in places where it is now winter, in Australia, New Zealand, Patagonia. Even in the cold and wet north, in Siberia, Iceland and Northern Canada, there are blazes seemingly everywhere.”

Of course, in Britain, there’s not much forest left to burn, its 13% coverage the lowest in Europe, its nearly-extinguished wildlife among the most impoverished in the world.

Roberts dreams of the Great Bear Rainforest of the Canadian Pacific Northwest, of its rivers so thick with salmon that they seem to overlap like fish-scales, of its bears fishing in the rich waters, their salmon-enriched scat fertilizing the forested hills for miles around, wild with wolves. The bears and the wolves are gone from Britain now, along with most of the trees and nearly all the salmon:

“This was part of the great border forest, home to the last wolves in England and Wales. There are few stories of them, though they were still here when some of the old oaks which stand in the fields were saplings.”

His wife recovers; Roberts’s depression doesn’t go away. He reflects on a saying of the psychologist James Hillman, that depression is sometimes a right response to a damaged environment; you may feel like that because that’s how things are, “a sign you’re still sane”.

The text is interspersed, accompanied and enriched, by full-page prints of Roberts’s evocative ink paintings. He uses ink, water, and salt which creates dark specks with paler surroundings, random but orderly, wild but controlled, like an ecstatic dancer following the choreographer’s steps but connecting with the hearts of the audience.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

I received a review copy of this book.

The team of two men were soft-spoken Irish and efficient, unflappable even when one dog after another came excitedly up to investigate the unusual scent. The actual moving of each batch of logs took a few seconds and was amazingly hard to photograph as most of the action was on narrow temporary paths among the trees. Of course that is exactly why a horse is better than a tractor, as there is no need to cut new roads through the woods to extract the lumber, and no danger of getting stuck in the mud either.