Amy Liptrot goes to live in London to escape the cramped life as a teenager on Orkney, a group of windswept islands off the north of Scotland. Her father was sectioned under the mental health act the day she left. At least she was free of the constant pressure from her happy-clappy Christian mother. In London, she parties, she drinks, she smokes, she takes drugs, she has sex. Is she happy? No. She drinks more and more, she loses one job, then another, then her boyfriend and her flat.

Something needs to be done. She’s not sure if she can stick with Alcoholics Anonymous’s talk of God, is that her mother all over again, but she tries it anyway and goes sober, along with the drug addicts and no-hopers:

“I had never injected drugs, been a prostitute, smoked crack in front of my baby, spent eight years in a Russian prison, mugged an old man in the park, or been through six detoxes and four rehabs, painfully relapsing each time. My family still spoke to me, and I had not turned yellow.”

She goes back to Orkney, still sober. A woman tells her she’s washed up: painful because not entirely untrue: but she’s on the mend. Her father’s farm had a small neat area of little fields near the farmhouse, and a big wild area where the sheep could graze, the outrun. Perhaps Amy had been away on her own outrun for those ten troubled years in London.

She stays with her mother for a bit in Orkney’s little capital town, Kirkwall. It rains for 54 days in a row in the winter; then at last some “dreamy sunsets reflected on calm sea”. She goes back to the farm and spends days building drystone dykes, thick heavy double-walls of stone. She rebuilds herself at the same time…

Greatly daring, and knowing nothing about ornithology, she applies to the RSPB to spend the summer mapping the distribution of all the breeding Corncrakes on the Orkney Islands. She gets the job. She spends the summer staying up all night, driving about and stopping the car to listen for the extraordinary “crex crex” croaking noise that gives the bird its Latin name.

She maps 31 of the elusive birds dotted about: one island has exactly one male bird. She sees a Corncrake exactly once in the entire period. Once, she arrives at a stone circle at dawn: nobody is about. She takes off her clothes and runs around it.

She discovers that the RSBP’s house on the island of Papa Westray is used to warden the bird reserve there only in summer. She asks if she can stay there in the winter. It’s not insulated, normally left empty then. She gets it: the rent is very low: “I decide that I will spend my time in the kitchen with the fire, leaving the rest of the house to the cold.” It’d be a perfect place to drink… nobody would know… but she stays sober. “There are no flatmates or close neighbours to hear me crying at night.” She recollects in tranquillity how she was sexually assaulted in London: she fought the man off, he was imprisoned; and how she crashed her car and was banned for drunk driving. She notices each day the

“moment, looking back, facing into the northerly wind … when my heart soars. I see starlings flocking, hundreds of individual birds forming and re-forming shapes in liquid geometry, outwitting predators and following each other to find a place to roost for the night. The wind blows me from behind so strongly I’m running and laughing.”

Her nephew was born soon after she went sober. “He will never see me drunk.”

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

You and I have read plenty of nature books that wax lyrical about the beauty of the liminal, the unfathomable gritty reality of walking along a muddy track on the outside of town between the sewage treatment plant, the football stadium, and the business park, and suddenly being transfixed etc etc by the unearthly and astonishingly loud song (for such a tiny bird) of the wren, rising etc etc above the mundane roar of the traffic and the air conditioning fans to transport the lonely naturalist into the unparalleled ecstasy of the mundane.

Fortunately, Two Lights is nothing like that.

James Roberts is an artist as well as a poet. He is lucky enough to live in the quiet countryside of the Welsh Borders: and to enjoy some of the country’s darkest skies, so that he can see thousands of stars, the milky way and comets. And he writes about it simply and beautifully. But no, he does more. He lets his imagination, his atlas of the world, the journeys he made when he was young, what he has read, his father’s decline and death from Parkinson’s, his wife’s journey through breast cancer and radiotherapy, history, the loss of wild places everywhere, take him to different places, and express what everyone is feeling in these crazy times, love and loss and desperation and, yes, beauty despite it all.

Roberts is an experienced artist, with the gift to describe his subject plainly without either getting excessively technical, or talking down to his readers: “Most artists are obsessed with space. Positive space is the area of a picture which contains the subject, the details, the face or figure in a portrait, the arranged objects in a still life, the trees and rocks in a landscape. Negative space is the area of the picture which surrounds the subject.”

He goes at once to the heart of the matter: “I’ve spent hours staring at Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, wondering how he managed to achieve the milky light in the room, the sense of silence, the open-mouthed expression on the pregnant woman’s face and the depths behind it.”

I don’t know about you, but I immediately downloaded an image of the painting – the book’s illustrations are all of Roberts’s own work – and spent several minutes with my new-found knowledge of positive and negative space, wondering how Vermeer had done it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy. Then I wondered how Roberts had written about it all so seamlessly, as if it was easy.

Two Lights begins with a chapter on the dawn, and ends with one on dusk, presumably the two lights of the title. Roberts says he is attracted to these times, these transitional lights, when forms appear or dissolve, when shapes shift, when negative space appears positive or vice versa, when birds sing, when what seems solid and permanent is revealed as constantly changing.

The book’s subtitle, Walking through Landscapes of Loss and Life, speaks of its themes: personal connection to a landscape and its wildlife, to all of nature; and within that, a connection between personal loss and the silent, invisible shockwave of human impact on all of nature, from the paleolithic to the present.

You might think that with global warming, deforestation, overfishing, soil erosion, draining of wetlands, damming of rivers, pesticides, pollution, growth of cities, nights so bright with streetlights that citydwellers never see more than half-a-dozen stars, nights without nightingales, corn without cornflowers, meadows without meadowsweet, hedges without “immemorial elms”, roadsides without primroses, garden Buddleia bushes without butterflies, the extinction of species… that we would need no reminding that we have lost something.

But Roberts is right, we’ve forgotten. Our leaders think of wars and armies, of immigrants and policies, of votes and elections, ignoring what is happening to the world all around them: like officers fighting on the bridge of a sinking ship.

He’s also right that lecturing doesn’t work. Perhaps the oblique, feather-light, razor-sharp insight of an artist and poet may do better.

Roberts walks the bare hills and valleys of Wales, recalling “the forest of my imagination … hiding beneath my feet, in these hills, waiting to regrow.” The trees were cleared thousands of years ago, the first people of Britain burning gaps in the forest to make way for their fields. Now:

“News bulletins have been covering fires in Greece and Italy, and also those in California … on the map, the brightest areas are in Africa. The whole of the Congo seems to be burning, Central and East Africa lit up, Zambia, Angola, Tanzania, Kenya. There are fires in places where it is now winter, in Australia, New Zealand, Patagonia. Even in the cold and wet north, in Siberia, Iceland and Northern Canada, there are blazes seemingly everywhere.”

Of course, in Britain, there’s not much forest left to burn, its 13% coverage the lowest in Europe, its nearly-extinguished wildlife among the most impoverished in the world.

Roberts dreams of the Great Bear Rainforest of the Canadian Pacific Northwest, of its rivers so thick with salmon that they seem to overlap like fish-scales, of its bears fishing in the rich waters, their salmon-enriched scat fertilizing the forested hills for miles around, wild with wolves. The bears and the wolves are gone from Britain now, along with most of the trees and nearly all the salmon:

“This was part of the great border forest, home to the last wolves in England and Wales. There are few stories of them, though they were still here when some of the old oaks which stand in the fields were saplings.”

His wife recovers; Roberts’s depression doesn’t go away. He reflects on a saying of the psychologist James Hillman, that depression is sometimes a right response to a damaged environment; you may feel like that because that’s how things are, “a sign you’re still sane”.

The text is interspersed, accompanied and enriched, by full-page prints of Roberts’s evocative ink paintings. He uses ink, water, and salt which creates dark specks with paler surroundings, random but orderly, wild but controlled, like an ecstatic dancer following the choreographer’s steps but connecting with the hearts of the audience.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

I received a review copy of this book.

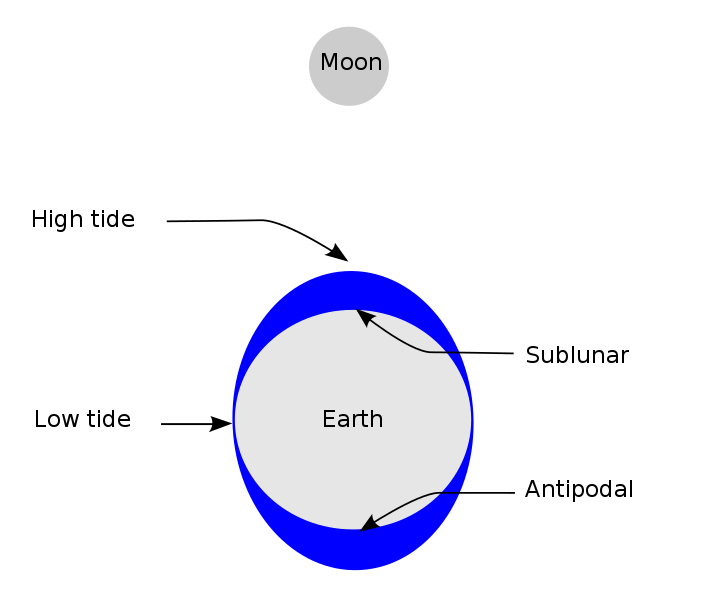

Chiswick Mall, like Strand-on-the-Green, is a low-lying riverside street here in Chiswick. At High Water on a Spring Tide, the streets regularly flood, but not always as much as this … and in 20 years, I never saw kayakers here before! So I was delighted to get this shot.

For landlubbers who’re a bit rusty on what a Spring Tide is, the tides follow the moon’s 28-and-a-half day cycle from Full Moon (opposite the sun) via half-moon (right angles to the sun) and New Moon (roughly in line with the sun, when eclipses sometimes occur). There is a high tide roughly twice a day (and a low tide twice also); every Full Moon, High Tide (High Water) is especially high, as the pulls from the moon and the sun on the oceans have maximum collaborative effect then.

Also on the walk, several Brimstone butterflies, and a couple of Peacock butterflies (presumably overwintered in a hollow tree or some such place). Near the sheep were two Buzzards and a Red Kite, on the lookout for some carrion, I won’t mention what they were hoping to find. Also about was an early Chiffchaff singing its simple song (its name, over and over), a Cetti’s Warbler, and a Song Thrush. And a flock of Goldfinches finishing up the last of last year’s seeds in a big patch of thistles, burdocks, and teasels.

Among the wonderful moments on this walk: a heron gave its cronking call and flapped slow over the water; a plane passed behind three cormorants drying their wings, perched on the branches of a dead tree; a group of goldeneyes panicked and pattered across the lake, gaining speed for takeoff, giving their high-pitched call, the waves sparkling in the slanting sunshine; a song thrush tentatively singing its repeated music; a solitary fieldfare.

Barden Moor is an extensive water catchment area, on acidic rock (Millstone Grit), providing soft drinking water to the city of Bradford. The area is part of the ancient Bolton Abbey estate, and is now also in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. It’s covered in heather and moorgrass with areas of meadow and bog pools. It’s a fine place for an open airy walk away from the sometimes busy mountaintops, and a wonderful spot for nature.

The presenters on Radio 4’s PM programme said that we needed an Awesome Nature Walk to lift our spirits during this renewed Covid Lockdown. Happily, we had already planned to go on one, and here it is: an Awesome Nature Walk at Wraysbury Lakes.

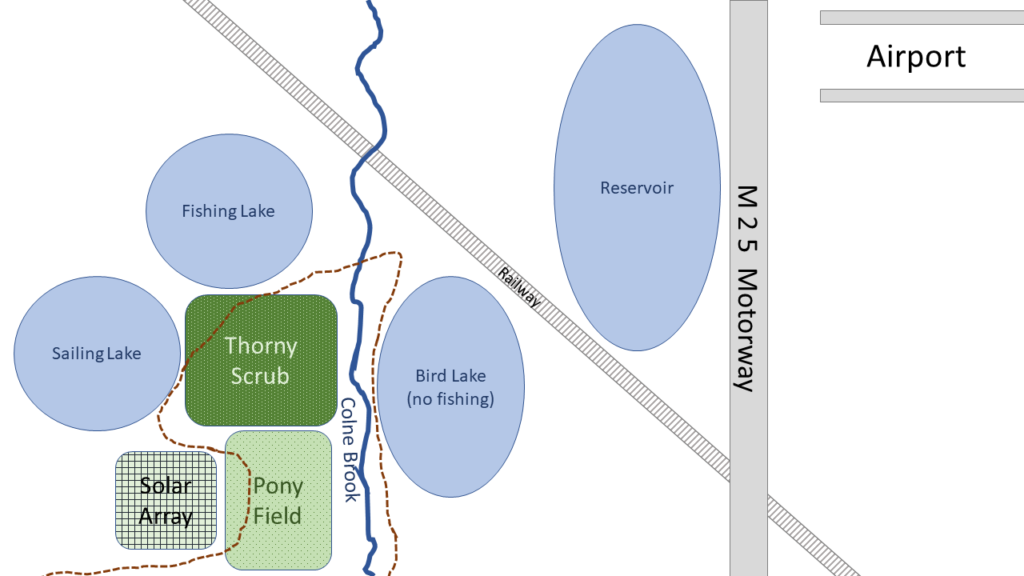

The walk begins near the road bridge over the Colne Brook at the bottom of the map, which is by a repair garage. I’ve drawn the sketch map to give something of the feeling of the route while I’m walking it, rather than attempting to make an objective map.

The area is just outside the M25 ring motorway that informally defines London’s boundary; Heathrow Airport is just inside that, so in normal times (hmm) there is a plane overhead every 90 seconds. Down on the ground, there are numerous lakes which all started life as gravel pits. The River Thames laid down great amounts of sand and gravel in its wide flood plain during the Pleistocene, and the various Flood Gravels now form valuable building materials. Extraction round here has finished, but there are active pits a bit further afield. The pits go below the water table so they fill up by themselves. The large Reservoir is a bit different – it has an enormous high earth bank all around it, so the water level is high above the surrounding ground level (maybe there was gravel extraction there too before the Reservoir was built). A railway runs across the area; it can be crossed at a pedestrian level crossing with a pair of stiles and a lot of looking both ways. To the south of the lakes is an attractive area of thorn scrub with Hawthorn, Dog Rose, Spindle, Bramble and suchlike, with quite a few trees, all very good for wildlife. Down by the lake edges and the Colne Brook are many large Willows and Poplars which grow quickly, lean over, fall, and sprout up anew, forming a constantly-changing cycle of growth and regeneration, and providing cover and roosting-sites for warblers and water-birds.

The lakes have variously been repurposed – one is used by the sailing club, though I more often hear the clatter of rigging vibrating against sail-less masts on windy days than people actually sailing. Another is a strictly private fishing lake, protected by fierce signs and fiercer fences which must have cost a fortune to put up. The lake by the start of the walk is open to wildlife and fishing is forbidden; a delightful trio of icons make it clear that running with a large carp under your arm is forbidden, as is spear-fishing (or is that a black line crossing out a standing fisherman diagonally); frying fish on a griddle is not allowed, though nothing is said about making fish stew in a saucepan, interpret the icon how you will.

South of the scrubland is a pleasantly scruffy pony-field with scattered thorn-bushes and rough grass dotted with tufts of Alfalfa. It rises to a low hill which was once a municipal landfill dump. For some years the dump was grassed over and the ponies roamed all over it; then men came and installed deep pipes to sample and carry away the presumably polluted groundwater; finally, a sizeable array of solar panels was installed and fenced off, complete with security cameras, so ponies and walkers had to make a detour around the array.

So — airport, motorway, gravel-pits, railway, landfill, post-industrial leisure activities, it’s pretty much the classic Urban or Peri-Urban nature area.

The bridge over the Colne Brook offers a glimpse of calm nature; the water babbles softly among the waterweeds, and two Kingfishers dark on triangular wings just above the surface. One swerves into a U-turn, catching the sun to reveal its brilliant blue-and-turquoise plumage. What a moment to start a walk.

We dive gratefully down the few steps from the pavement to the path: the pavement by the bridge is half-occluded by unclipped bushes, and the traffic whizzes past perilously close to unwary walkers.

In the sudden quiet we peer through the trees to the lake. A gang of twenty Cormorants is on the water, with a group of Mute Swans.

The path is bordered with Willows and coarse herbs; a patch of colourful Comfrey, once used to help knit broken bones, attracts some Common Blue Damselflies. At a gap in the Willows, a Cetti’s Warbler sings its abrupt, loud song. Some Migrant Hawker Dragonflies scoot too and fro beside the water, their transparent wings whirring, their long slender bodies glittering blue.

We come to a patch of reeds where we can see right across the lake. A Chiffchaff flits between bushes. On the far side is a bank of Willows, several with protruding dead branches. Perched on these are a few Grey Herons, half-a-dozen Cormorants, and most excitingly three Little Egrets — small white herons with black legs and yellow feet: uncommon visitors here. All of these are predators, feeding on fish and small animals like frogs; the Cormorants fish by diving from the surface, while the herons stand by or in the water, looking out for prey.

The track through the thorny scrub is bright with Rose and Hawthorn fruits — “Hips and Haws” in the fine old country phrase, rich with double entendre, glowing in different shades of red. Across a wide patch of Teasels and Burdocks and Thistles, all tall and prickly in their differing ways, more Hawthorn bushes are still in green leaf but bursting with red fruits, so they are red and green at once, which you might have thought impossible, but there it is, spectacular.

We swing through the kissing-gate and into the pony-field. The animals barely glance at us, the rich grass is clearly far more interesting. “Alfalfa” apparently means “King of Herbs” in Arabic; it was supposedly the finest pasture for grazing animals from goats to camels.

The path rounds the Solar Array; I guess it’s good to know that more and more of our energy is renewable, even if an Electric Vehicle, with its large price-tag, doubtful driving range, and complicated charging arrangements if like me and many city-dwellers, you don’t have a front drive to park and charge it on, is still perhaps a bridge too far. It does feel as if, with one more push, there could be charging points everywhere and affordable prices, and suddenly it’ll look not exotic but obvious. Five years, maybe? Who knows, but at least it’s coming.

This is a powerful book, one of the few on nature that can simply be called great. Perhaps Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring was the last one.

McCarthy states that nature is under deadly threat from humanity. We build roads, dams, sea walls, houses, factories; habitat is destroyed. We drive cars, fly in planes, live in houses made of brick or concrete; oil is burnt, releasing carbon dioxide, causing global warming. The extra heat warms the oceans, making sea level rise. The carbon dioxide makes the oceans acidic, threatening species-rich coral reefs. We buy food containing palm oil: the palm plantations march across the tropics, replacing species-rich rainforest. We eat hamburgers. Cattle grazing spreads across the world, replacing more rainforest; methane from cow stomachs joins the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. Every habitat is under attack. A 6th extinction, to rival or exceed the great extinctions like the Cretaceous-Tertiary which destroyed the dinosaurs, is under way already.

McCarthy tells what this means in his own experience, his own country, England. When he was a boy, Buddleia bushes in the suburbs were covered in butterflies: now they aren’t. When he was young, car headlights and windscreens were covered in insects; any night drive in the country seemed to be through a blizzard of flying insects, the ‘Moth Snowstorm‘ of his title. Now, if he sees one moth, a single one, on a journey, it is worthy of note. Nature has been thinned out, not quite to extinction in most cases, but the great, joyful abundance is gone, in one lifetime. Half the farmland birds are gone. Common sights like a field of lapwings, a street of house sparrows, a tree full of starlings, are no more.

Nature matters, McCarthy writes, not just for worthy reasons of biodiversity conservation, or even for pragmatic ones like pollination of insect-pollinated crops like beans and apples and cherries by bees tame and wild. Probably, he suggests with grim humour, some scientist is even now hatching a crop plant that won’t need pollination: even honeybees may soon be redundant.

No, he argues, we need nature because our species, Homo sapiens, grew up with it for 50,000 generations. We feel well in nature, on a walk by a river, in the hills, in meadows with flowers and butterflies in the sunshine, on a wild coast whether of cliffs or salt marshes, with thousands of wading birds in great clouds, the wind on our faces. In a word, nature brings joy. Without it, life is sad and grey, missing something vital, whatever the distractions offered by online shopping and instant messaging and all the rest.

Joy, argues McCarthy, is the one thing that can motivate people to fight for nature. Given that it’s threatened, we need a powerful, universal feeling to drive our politics. As the human population rises and pressures mount, as global warming bites on every continent, we will need to fight hard to keep whatever’s left of nature alive. Our survival, the survival of whole ecosystems and millions of species, depends on it. We need, urgently, to teach people to love nature, for which we need reserves, in cities and outside them, where people can experience the joy of nature for themselves; where children (and adults) can walk and run and play and pond-dip and bug-hunt and laugh and see frogs and foxes and butterflies. Then, and only then, can we urge them to fight.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)