The usually clear lake was covered in thick green patches of weed, enough for Coots to be able to walk on.

The path, too, looked rather different, with many of the large creaky poplars cut down leaving a wide unfamiliar swath of bulldozed path. The poplars constantly drop branches and fall over so it was about time.

There were not many insects about – Emperor Dragonfly, Migrant Hawker, Common Blue Damselfly (with the ace-of-spades on segment 1 of the abdomen), Green-Veined White, a few Speckled Wood was about it.

I don’t recall seeing much of that troublesome weed of nature reserves, the Himalayan Balsam, but it was evident in cleared areas. Shame it’s a nuisance, as it’s rather a beautiful plant.

Warm September weather usually means no migrants as they all settle down to enjoy the last bit of summer before moving. I heard a Cetti’s Warbler and a brief unseasonal burst of Chiffchaff song; I think I glimpsed a Blackcap diving from a patch of Teasels back to its bush. A few Jays shrieked and flapped butterfly-like across the horse pasture. A lone Kestrel flew lazily to perch in a tree. On the water, not much apart from Coots, a Mute Swan, Mallard, a family of Egyptian Geese, some Cormorants (quite a few of them with a lot of white on their fronts).

An Apple tree glowed with nice ripe fruit; someone had beaten a path under it to do a little picking.

London does look beautiful at night when seen across the river, whether you look at the classical outlines of St Paul’s Cathedral – not the one that Shakespeare knew, of course – or at the brash towers of the City, the slick take-your-money confidence of quick men who know all the patter and have the steel, glass and concrete to prove it.

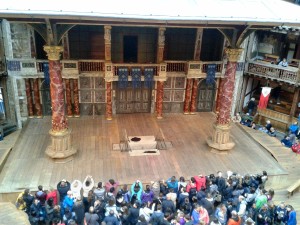

Everyone knows Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage” speech from As You Like It, and when that appears on stage as it did yesterday, it’s striking to see how well the strutting and fretting of the actors can work on that big wooden rectangle “in the round”, surrounded by the beautifully reconstructed circle of the Globe Theatre with the long-suffering audience standing in the pit. As you can see, we decided on the more comfortable course of seats in the upper gallery, affording a fine view of the pit audience reaction as the actors come right up to them, sit with legs dangling over the edge of the stage, walk round behind them, or actually push straight through the crowd.

But perhaps the Nature’s Book aspect of As You Like It is not so obvious:

Nature speaks to the (banished) duke in the Forest of Arden (Act II, Scene 1): the trees talk, the brooks babble as if reading, the stones deliver sermons. Here is the voice of Nature with a capital N, “the classroom, the library, and the church“, figured if not quite personified as pastoral wisdom.

In Shakespeare’s time, the Book of Nature was a “theological commonplace” (Paul J. Willis; JSTOR, library or subscription needed). The curious concept of nature more or less literally as a book

‘”originated in pulpit eloquence, was then adopted by medieval mystico-philosophical speculation, and finally passed into common usage,” where it was “frequently secularized”‘.

Nature is described as good in Genesis chapter 1, and Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Romans argues that God’s power is seen by the creation of the world and in his works. Willis observes that this is a bit difficult to reconcile with Paul’s assertion that nature is utterly fallen and sinful, but no matter. Willis concludes by noting the “often recurring comment” that As You Like It mocks the pastoral while basically enjoying the pastoral quality, and suggests that Shakespeare similarly mocks the rather lofty Book of Nature theme “without tossing it aside”. The comedy comes from realizing that the forest is an imperfect divine text, just as we are “faulty readers” of that book. “The result in this rich comedy is the book of nature as you like it, a forest that exposes both God and man.”

Having written a book on the English view of Nature, I find Willis’s analysis – and Shakespeare’s treatment – extraordinarily good.

Right in front of Mike the new conservation officer was a Wasp Spider. Of course, arriving late after working on scenarios for the new hut, I noticed it – her – before he did. The species only arrived in Britain about 15 years ago, and it’s certainly spreading.

Anthill ants are supposed to be minute, yellow, and never appear above ground. If so, these weren’t them. While we were digging brambles out of the anthill meadow, as gently as possible because the anthills are said to be one of the best features of the reserve, we couldn’t help disturbing some nesting ants a little. They seem to be black with grey abdomens; and as you can see, they quickly picked up their white cocoons and carried them off to safety. They certainly look as if they’re the owners of the anthills, but since the anthills are supposed to have been made by little yellow ants, perhaps the black-and-grey ones are just enjoying the resulting environment.

Several inch-long grasshoppers took a look at us.

I was lucky enough to catch an Emperor Moth caterpillar in the act of preparing to pupate; the full-grown caterpillar with its hairy aposematic yellow-green body marked with black is tied on to the grass stems with a hundred silken threads.

On the summit ridge, this flat rock was covered with magnificently coloured lichens in shades of orange, yellow ochre, grey and white, with black, grey, brown or burgundy apothecia.

Towards the end of the eight-and-a-half-hour walk with the sun westering low over the hills, we caught sight of a herd of 32 hinds. The little Nikon captured this nice shot of them, all peering down at us from the skyline.

After a morning sheltering inside from the pouring rain, it cleared and I drove down to Creag Meagaidh, the enormous national nature reserve that fills a watershed from Loch Laggan up to the named mountain. The sun shone nearly all the time despite billows of cloud to the south. The hills were blue, setting off the shining grey-green of the birches, the russet of the heather – the Ling just coming into bloom now – and the bright yellow-green of the mossy grass.

The Downy Birch is a stockier tree than the Silver Birch, tough enough to survive mountain winters, and home to a rich variety of lichens including Usnea beard lichens, bristly Ramalina, dark stringy Alectoria jubata (now renamed Bryoria fremontii), and various leafy Parmelia species that yield orange dyes used in Harris Tweed.

Large handsome caterpillars of the Northern Eggar Moth, the Scottish form of the Oak Eggar (Lasiocampa quercus), up to 3 inches (75 mm) long and nothing to do with oak trees, wriggled across the path, their rufous hairs warning off predators. They feed on Heather and Bilberry.

In every patch of damp grassland, Scotch Argus butterflies skittered, looking very dark in flight. They are hard to approach as they constantly chase each other off from their territories, but eventually I found one that stayed settled long enough to creep up to. Close up, the upper side is a rich brown, with red patches around the wing edges dotted with black circles that have white centres.

A few bumblebees, some of unfamiliar species, visited the Devilsbit Scabious (Scabiosa succisa) briefly. Large Syrphid hoverflies basked on the paths.

Further up the valley, a fine group of birches actually glittered in the bright sunlight, the water of the stream shining silver behind them.

A dead birch, stark against the sky, supported stout Birch Bracket polypores, handsomely whitish-grey above, yellow ochre below.

In the boggier patches, Bog Asphodel and Marsh Orchid flowered among the Bell Heather.

I turned the corner of the valley to see snow still lying in the deep, north-facing gullies on Creag Meagaidh, and the striking notch of the col that gives access to the mountain ridge.

Today I went for a proper nature walk, after cutting a lot of thistles on the farm in the morning. The birchwoods were lovely with Chanterelles, red Russulas, and the first few Orange Birch Boletes of the year.

The sun came out from time to time, enough to make the Spey Valley look lushly golden against the green wooded hills and the distant blue Cairngorms, the heather richly brown in the foreground.

I climbed up the old mossy boulder-field of fallen rocks until I reached the old-growth Hazel woodland, and sat down. Around me, a Spotted Flycatcher brought flies to a juvenile, and a pair of bright yellow Wood Warblers flitted about the trees and showed themselves beautifully. The rocks were richly lichened, and Wild Thyme and Wood Sage (elegant spikes of green flowers with purple anthers) sprouted among the ferns. Maidenhair Spleenwort grew here and there among the rocks. It was really pretty.

Then I made my way right under the last of the cliffs around to the north and up on to Creag Dhu itself, with glorious views over the Upper Spey valley. Half a dozen feral goats played the role of herbivore, along with a Roe deer that skipped away from me effortlessly up the mountain and over a crest.

As I neared the summit, a Peregrine Falcon, wings like an anchor, hung motionless in the stiff wind before swooping to the ground.

Back at base, we had a magnificent mushroom sauce on our rice for dinner.

I’m used to seeing Marsh Orchids up here in Scotland, but I’d always associated the Fragrant Orchid with chalk and limestone. However, I keyed it out with James Merryweather’s very helpful Key for the Identification of Orchids Common in Western Scotland, and there it was, Gymnadenia conopsea, growing among the heather and bilberries with no chalk in sight. Its jizz is quite unlike the Marsh Orchids, with slim unspotted leaves, pale unstreaked flowers, and an unobtrusive long slim spur behind each flower.

The Marsh Orchid is quite variable, usually boldly marked like this one in purple with stripes and loops, but sometimes almost white all over. It’s mostly rather short. The paired pollinia are visible inside a couple of the flowers.

Another little plant that I’d not have associated with rainswept moorland is the Birdsfoot Trefoil (or, Bacon and Eggs from its rich red and yellow colours). It is happy in warm dry lawns; but equally at home here on disturbed ground where the competing plant cover is conveniently low.

More obviously Highland in character are the tough lichens forming orange and black patches actually in the hard weathered rocks on the moor. The black discs are the apothecia of one of the species, containing the spores of the lichen fungus; they have to meet up with the single-celled algae to re-form the lichen partnership or symbiosis.

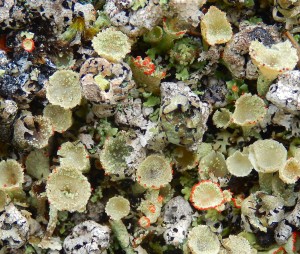

The miniature world of lichens is able to surprise even people who know their local environment well. The Cladonia ground-living lichens include shrubby species that make excellent tiny trees for railway modellers and architects. The same genus contains several species of cup lichens, some coarse and scaly like the common cup lichen (C. conoiocraea), some tall and slim like C. fimbriata, some with elegant red apothecia around the edges of their cups. This mixture of lichens, including some leafy grey Parmelia saxatilis, was growing on a rock beneath a light canopy of Downy Birches.

In the old system of transhumance, the women and children took the cattle up to hill pastures and lived in shielings during the Highland summers. These are marked today by small rectangles of grey stones, all that is left of the humble buildings, and bright green grassy areas among the brown of the heather.

The Antler Moth is sexually dimorphic, the female being larger and with a slightly different wing pattern. Appropriately for a species that shares its moorland habitat with the Red Deer, it has a whitish antler pattern on its wings. The caterpillars eat purple moor-grass, sheep’s fescue and matgrass.

It was a day for signs: we worked all morning digging two deep post-holes for a new welcome signboard beside the ramp path, telling stories as we dug down through dry soil, pebbles and then soft clayey subsoil. Eventually we were deep enough and level enough to pop the sign in, and with nothing more than the spoil, pebbles, and a spirit level and a bit of tamping, we had a fine new signboard up. As if by magic, the TV camera team from ChiswickBuzz arrived to film us holding up spades, a Green Cross banner (some sort of quality of service award), and asking us to cheer improbably, so we shouted 1-2-3 Hooray! and waved spades like idiots, and the camera crew looked happy and wandered off.

There were some bright black-and-yellow insects about pretending not very convincingly to be wasps, but their warning signs seem to work pretty well. After lunch we came back past the signboard to do a butterfly transect, and we nearly cheered as a visitor took a good look at the signboard. We joked that with an apostrophe missing, we’d have to dig the sign out and send it back for a refund.

On the transect we had good numbers of butterflies, but without so much sunshine it was without the masses of Gatekeepers of a fortnight ago. There were a pair of Commas, a Red Admiral, a Brimstone, and plenty of Small Whites, Speckled Woods, Holly Blues and Gatekeepers. A pair of (Migrant or Southern?) Hawkers scooted about from the hut to the ramp; down by the pond was an exuviae of something like a Broad-Bodied Chaser; a Common Darter sunbathed on the boardwalk, and a pair of Azure Blues wandered above the now happily full pond, laying eggs. The reserve echoed to the crash of demolition from the High Street.