The whole of the wetland was sparkling with Emperor Dragonflies patrolling the pools: a few females laid eggs by Water-Lilies, the males occasionally chasing prey, or a rival. The margins were full of Azure Damselflies, nearly all males: I saw one pair in wheel formation.

Several Red-Eyed Damselfly males displayed on lily-pads, chasing off rivals; occasionally an Azure came by too. Over one or two of the smaller pools, a Hairy Dragonfly patrolled; one of them had an aerial tussle with a similarly-sized red dragonfly, I think a Common Darter.

Overhead, quite a few Sand Martins caught insects over the water (well, the Wetland Centre does sport West London’s only Sand Martin bank, an artificial river cliff), along with a few Swifts, and I think exactly one Swallow … it feels as if something terrible has happened to these populations. They have to migrate across the Sahel, the Sahara, the Mediterranean, and numerous populations of hungry village boys and keen shooters, so it’s something of a miracle there are any left: and that’s not even speaking about climate change.

A couple of Common Terns, presumably those breeding on the Wetland Centre’s lake islands, made their bright and cheery waterbird calls as they wheeled about, searching for glimpses of tiny fish to dive in and catch.

There were only a few butterflies about – a Red Admiral, a Holly Blue, a couple of Speckled Wood, some Whites, a female Brimstone. For me, the bees and pollinators looked well down on normal, too. Amidst the warmth of the day, the beauty, the peace, and the brilliant colours, it is a sombre tale of decline.

A few years ago, BC (Before Covid), a major fire burnt many of the Pines and Birches that had invaded the heathland of Thursley Common; and unfortunately, the fire took hold on the wooden boardwalk that crosses the national nature reserve’s marshy area, and destroyed nearly all of it. This mattered, as everybody enjoyed the open airy walk, summer or winter, across the flat expanse with its rare habitats for Southern England — acid bog, bog pools, heath — and its rather special inhabitants, including lizards (and snakes), many species of dragonfly, marsh orchids, bog asphodel, skylarks, curlews, and more. Suddenly, visitors were confined to the edges of the reserve.

Well, people agreed the boardwalk must be rebuilt, and finally, here it is.

The wooden substructure has been replaced with posts and joists of recycled plastic. This artificial wood costs more than real wood, but will with luck last for many years: it’s invulnerable to rot, at least. Whether it’s actually friendlier to the environment is an interesting question: at least it doesn’t constitute new use of fossil fuels, or at least, not terribly much; wood is of course a fully renewable resource, as long as it comes from properly managed forests like those in Northern Europe. It could mean less maintenance and disturbance to the reserve, as it should need to be dug out and replaced far less often.

Fire is clearly now a sensitive matter on hot sunny days, with the unfamiliar sight of a Surrey Fire and Rescue Service truck patrolling the reserve, presumably to forestall any barbecue or picnic stove fires. There has recently been a serious fire across the road on Frensham Common, so the danger is close and real. We received a professional drive-by glance as we ate our definitely-cold sandwiches beside one of the bridleways. It’s interesting to see fire-watching in action here in Britain; in America, it has been going on for a century, and its effect there has been to allow the build-up of an enormous reserve of dry timber and brushwood across the national forests. That has been followed, one might think inevitably, by major fires that have burnt far hotter, for longer, and over much larger areas than previously.

When I lived in Suffolk, it was a common practice among the older local people to go for a picnic on the heaths on a nice sunny day; and when the thermos of tea had been finished, to set fire to a little bit of the heath, which then smouldered and burnt quietly in an unobtrusive sort of way, removing the taller bushes of heather and gorse, and probably some small saplings into the bargain. This does little damage to the wildlife, and in fact favours (rare) heath over (common) trees, effectively managing the habitat by interrupting the ecological succession to forest. As such old-fashioned, seemingly casual management has fallen out of fashion, fire has become more and more of a problem. Of course, with global warming, hotter summers and lightning strikes become more and more likely, so large and destructive forest fires are becoming more frequent.

So, I’m not averse to seeing the fire truck: nobody wants to have another disastrously hot fire on this common or any other. But fires will happen, and better many and small than few and hot. So perhaps the fire-watching needs to be supplemented by a little carefully-managed fire-setting. Let’s hope that’s in the reserve management plan. Without it, woody plants can be controlled by cutting — for instance, a tractor can mow heather to remove excess wood and cut small tree seedlings — and by grazing, and indeed there are some grazing areas at Thursley. But anyone who looks at the common will see a mass of invading Birch and Pine saplings, and they may well wonder whether the current management regime is sufficient.

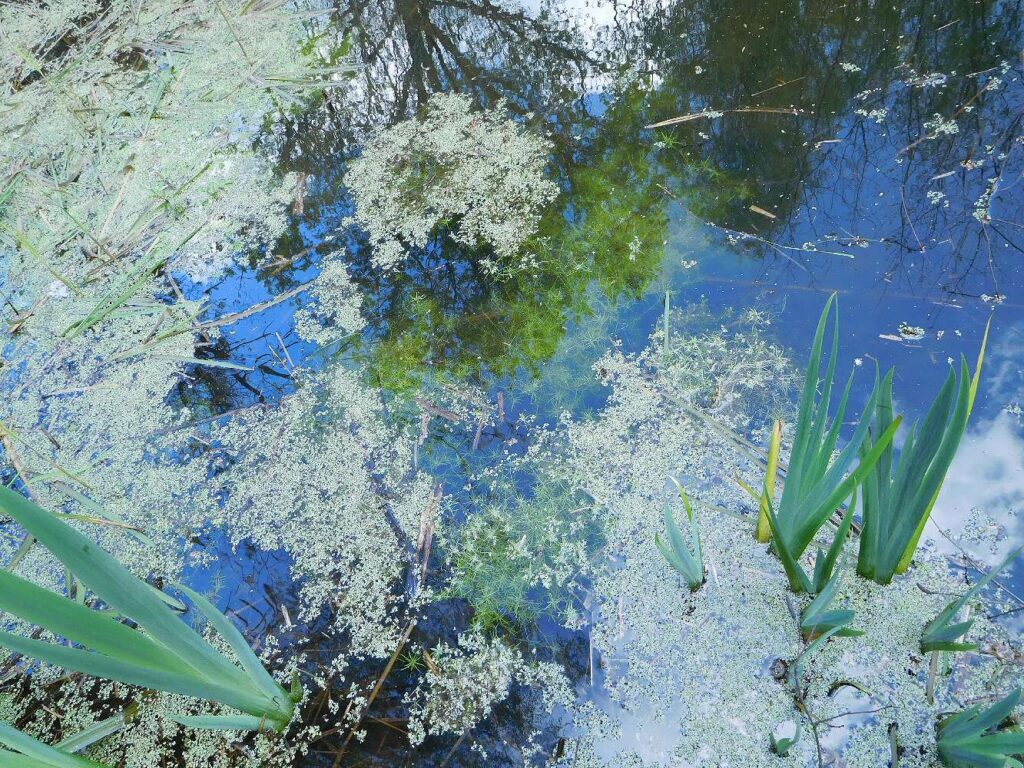

The pools were alive with sparkling dragonflies, really difficult to get binoculars on to, as they flashed, dashed, darted, chased, and flickered to and fro, defending territories over the best bog pools and floating vegetation. I was delighted to find a group of Downy Emerald Dragonflies strutting their stuff over the glorious water lilies in Moat Pond. The bog pools also harboured Black Darters (more often seen in Scotland than the south of England), Broad-Bodied Chaser, Four-Spotted Chaser, Common Blue Damselfly, and a Banded Demoiselle. More than likely there were several other species present but as they hardly ever settled, and as the brisk breeze gave them afterburner-speed, it was not easy to tell.

London Wildlife Trust’s ecologist, Alex, has set about finding out what is actually happening to multiple sorts of wildlife across the Trust’s many reserves, including quite a few that don’t have a warden, or even a group of volunteers. This is quite the task, when you consider that each reserve may contain multiple habitats — woodland, meadow, and pond, for instance — and that each habitat may be monitored for different sorts of beastie, like amphibians or pond invertebrates, and that each site may be sampled in each of several places (different ponds), each with multiple micro-habitats (open water, between plants, …), and each sampled repeatedly through the season.

Alex has set up templates for each type of monitoring in the Memento Database app, which has the merit of being free to download, and of being usable entirely offline if people are saving their mobile’s battery or have a wobbly data connection. We downloaded the app and installed her ‘Aquatic invertebrates’ template.

Then we half-filled a plastic tray with pond water and told the template to create a new sample record. We put in our initials, agreed a numbering for our four ponds: the seasonal ponds P1, P2, P3, and the main one P4, and filled in the amount of shade on the water, amount of vegetation, depth of water (the net handle came in handy here as a depth gauge) whether there was rubbish or dead wood or signs of eutrophication or a few other parameters, and then looked VERY carefully at the “water” in the tray to see if there were any beasties in there BEFORE we’d collected our carefully-taken sample. So if you find 5 Daphnia water-fleas in there, you have to subtract that number from your sample when you count it…

One of us — Andy or me — then took the net, swished it about in the chosen area of the pond for 3 seconds, and brought the sample to the tray, carefully washing the net in the tray water.

The template had been constructed for Android. Andy had an interesting time working out how to use it on his i-phone. On my Android phone, it turned out to be a good deal simpler to use, though with three tabs to complete, each with a long list of fields of various sorts, and a nearly invisible SAVE button (the critical bit, really), it took a little practice to get used to it.

The other requisite skill, of course, was being able to see and recognize the little beasties in the water. I thought I’d have no difficulty as I know my Midge larvae from my Mayfly nymphs: but a large number of the pondy bestioles (all technical terms here) turned out to be extra-small water fleas too small to make out clearly without reading glasses (at home, naturally), and too deep in the water to focus on with my hand-lens. So for next time, glasses, and my oversized Sherlock Holmes magnifying glass that someone gave me when I was a teenager — absurdly low magnification, but a wide field of view and a large depth of field. Aha.

The smidgeon-sized millibeasts on which the survey depended (at least on this lovely April afternoon) were the tiniest Daphnia I’d ever seen; equally tiny Cyclops; and (if possible) even smaller Water Mites. My first reaction was, we’ll never manage to ID those things, let alone count them. But you know what? It’s possible, even with a bit of presbyopia. How? Well, the trick is to rely on the “jizz”, the plane-spotter’s “general impression, size and shape” (yes, that must have been “giss” originally, but pronounced jizz anyway), i.e. how it moves, what sort of smudge of colour you can make out, and any hints as to what shape the thing would have if you were actually able to pop it into a watchglass and peer at it properly with a binocular microscope (at home, advisedly).

Daphnia are basically oval, and have a slight reddish hue to them. Cyclops are slender, tapering to a point at the tail, and look greyish. If you’re really lucky, you get a female Cyclops with a pair of obvious egg-sacs either side of her tail.

So you can tell Daphnia and Cyclops apart even if you can barely make them out, because they give a different impression. And, Daphnia swim on their sides, thrashing along with their feathery antennae; while Cyclops swim on their bellies, flicking their antennae like an athlete doing butterfly-stroke with their arms. Both therefore move in little jumps or saccades. The other micro-bestiole that we had in numbers today was the Water Mite. They’ve got 8 legs and a basically round body (the head does not protrude). They swim with their little legs, rather smoothly and continuously … so they don’t look anything like water-fleas except in size.

So we counted the animals in each sample. Coming to the main pond was a pleasure, as it’s a beautiful spot; the sun was warm; and the first thing we saw (rising to the surface of the pond) was a nice big male newt, the first of the year. More, Alex identified it as a breeding Male Palmate Newt, not our usual Smooth Newt: its tail goes down to a point, making it seem relatively short, and its hind feet are webbed.

I added it to the “Notes” field (this was a record of invertebrates). Andy and I found that we were getting used to the template, and filled it in a lot more quickly than our first efforts. I saved and exported the sample record to a .CSV data file, and pressed the email button. To my astonishment I only had to make a couple more clicks and the whole dataset sent itself off to Alex for analysis.

For many years, we – London Wildlife Trust and its volunteers – have mainly tried to keep Gunnersbury Triangle open and usable: the paths not blocked by fallen trees or too tightly hemmed in by encroaching brambles, edged variously with low fences, deadhedges, a ditch or two. lines of loggery posts to nudge people to stay on the path while giving the stag beetle larvae a bit of habitat, or failing all else just long heavy logs laid on the ground end to end.

Apart from that, we’ve done what we can to stop the meadows vanishing under bramble, repaired or replaced benches and boardwalks, and left the rest of the reserve more or less to its own devices.

That has meant that much of the reserve has been heavily wooded, with a rather dense canopy, a shaded woodland floor, and a mass of ivy and bramble that has got pretty much everywhere. That’s a class 3 or degraded woodland, where the ideal is a pretty and species-diverse floral ground cover – a bluebell wood, say, or dog’s mercury, or any of the flowers adapted to pop up in spring before the deciduous trees that form the canopy come into leaf and cut out the light to the smaller plants beneath them.

Well, at last we’ve started to have a go at habitat restoration. The areas most suitable for the effort are those where the tree canopy is thinnest, so forest floor herbs have a decent amount of light throughout the summer. The north bank is clearly an ideal choice here, as it’s south-facing and in many places relatively open; it’s also less likely to be trodden down because of its steepness. If it has a disadvantage it may be that it’s very free-draining, and may get dry quickly in a hot summer.

Be that as it may, we’ve now spent a couple of sessions digging out brambles, clearing dead wood, and pulling the ivy from the ground. A heavy metal rake makes quick if tiring work of removing the ivy. With all the rain we’ve had recently, all but the biggest brambles come out satisfyingly and permanently by the roots when pulled, which they certainly don’t in a dry period.

In the photo above, you can see an uncleared bit of woodland floor on the right, and a cleared area on the left. We managed to clear a 30-foot length of the north bank in one session today. Maybe we’ll get all the way up to the rather fine bluebell patch next time.