I suppose you are familiar with the ghettoisation of Britain’s towns and cities. To take a few rather random examples, Bath, Bradford-on-Avon, Edinburgh, Marlborough and Oxford are seen as ‘nice’ (terrible word), become populated with the middle class, Waitrose, estate agents and boutique shops, and suffer enormous rises in house prices, while nearby places are seen as less desirable, acquire sink housing estates, crime, and scruffy concrete jungles where once there were perfectly decent town centres. Areas of London do the same, but in a more rapidly shifting way, as the sheer pressure of population, and the desperate shortage of housing, forces people into scruffier areas which thus become ‘gentrified’ (though hardly by landed gentry, actually).

Perhaps the ghettoisation of nature is a little less familiar. As a boy, I was allowed out to go and do as I pleased in between meals (ah, those happy days when we didn’t know about paedophile celebrities: mind you, nobody is actually suggesting they stalked the countryside attacking random children, they had more subtle means of approach. But I digress). We used to go down the stream and build dams — the farmer never seemed to mind, and I guess our small engineering works of sticks, mud and stones never lasted long. It was tremendous fun watching the water well up, and exciting to run for more materials as the level rose and the water found new places to escape; I don’t think we ever tried to construct an intentional spillway anywhere. Or we wandered out in autumn to gather blackberries, returning with heavy plastic bags full of the squashy fruit, demanding blackberry-and-apple pie for supper like latter-day Peter Rabbit siblings. We scarcely remarked on the Yellowhammers in every hedge, Song Thrushes in the woods, Lapwings, Skylarks and Grey Partridges in the open fields: they were just there. There were Spotted Flycatchers, Swifts and House Martins nesting in the village, too; we noticed these last as the upstairs windows couldn’t be opened for months to avoid breaking their nests.

Leaving aside whether parents will allow children to go out unsupervised nowadays — kids have to learn to take care of themselves eventually, and the sooner they learn to be sensible, the better, specially if they have fun and play adventurously at the same time, a visit to the countryside today will, on average, involve less than half as many farmland birds as in 1970, and far fewer than that in the case of Lapwings, Skylarks and Grey Partridges. The countryside has emptied of birds — and of bumblebees and primroses and much else.

Instead, if you want to see Nature (the capital letter is intentional) you go to an official Nature Reserve. If you want to see a traditional village you study the web or the official Heritage handbook, fuel the car, pack a picnic, and travel to the official Heritage site, or rather to the official Heritage car-park complete with high-visibility-jacketed attendants and ticket machines, and walk down the officially landscaped path (keep off the official bit of woodland with bulbs underfoot to the officially declared bit of Heritage. It looks pretty attractive, but for the hordes of amateur photographers taking pictures of hordes of amateur photographers, ice-cream lickers, picnickers, dog-walkers, beer-swillers and motorcycle enthusiasts (why do oily chains, throbbing Harley-Davidsons and polished chrome go with pretty places? Answers on a postcard, please) in every street.

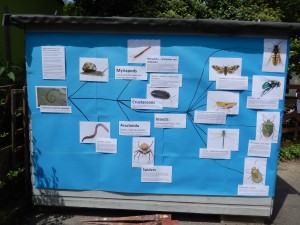

The official Nature Reserve also has a car park, which is at least generally free, at least to members. There is a big official sign with a colourful map, sometimes painted with happy butterflies, frogs, foxes and woodpeckers — the more conspicuously coloured species seem to be favoured in this form of natural selection, perhaps aposematism has something to do with it. There are quite often free maps and nature trails, even colouring sheets and clipboards for crayon-carrying children. Sometimes the trees and flowers are officially labelled as well, complete with Heritage notes about what Comfrey used to be grown for in the days when real people lived in the countryside (it was to help healing of bones, if you’re curious), or what Hazel coppicing was and why it was practised (tufts of small straight flexible wands, cut and used to make hurdles to fence in animals temporarily, and so on).

All of this effort is quite admirable in its way: relaxation, getting out of the house for the day, being together as a family, learning a little history, a little about nature. But what has been lost in the process is more striking: freedom, simple personal discovery and exploration (think blackberry-picking, dam-building, just coming across birds singing and bees buzzing). Don’t get me wrong, given the lack of nature in ordinary farmland there is a pressing need to rescue at least some areas of habitat; and given people’s cramped urban lives, it’s right they have some attractive places to visit. All the same, Nature, like Heritage, is being ghettoised. The process has not yet run to completion in Britain — there are still magnificent areas of mountain, moorland and coast where you can wander free of twee signs and uniformed attendants — but the paraphernalia are spreading: you can find them on Access Land in Northumberland, for instance.

As Joni Mitchell sang long ago, “Take all the trees / Put ’em in a tree museum. Charge all the people / A dollar and a half just to see ’em. Don’t it always seem to go / But you don’t know what you got till it’s gone. / They paved paradise, put up a parking lot.”