The presenters on Radio 4’s PM programme said that we needed an Awesome Nature Walk to lift our spirits during this renewed Covid Lockdown. Happily, we had already planned to go on one, and here it is: an Awesome Nature Walk at Wraysbury Lakes.

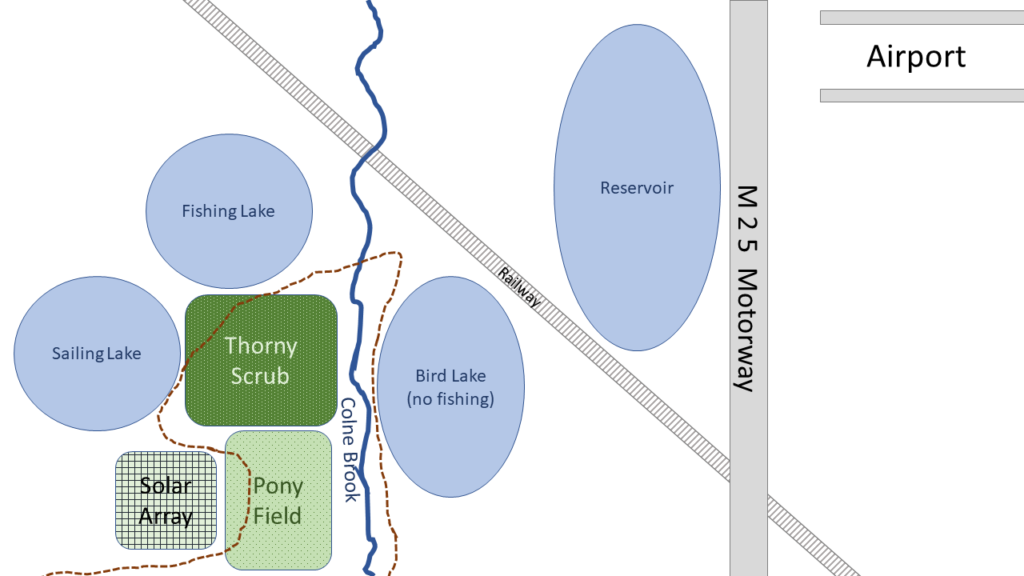

The walk begins near the road bridge over the Colne Brook at the bottom of the map, which is by a repair garage. I’ve drawn the sketch map to give something of the feeling of the route while I’m walking it, rather than attempting to make an objective map.

The area is just outside the M25 ring motorway that informally defines London’s boundary; Heathrow Airport is just inside that, so in normal times (hmm) there is a plane overhead every 90 seconds. Down on the ground, there are numerous lakes which all started life as gravel pits. The River Thames laid down great amounts of sand and gravel in its wide flood plain during the Pleistocene, and the various Flood Gravels now form valuable building materials. Extraction round here has finished, but there are active pits a bit further afield. The pits go below the water table so they fill up by themselves. The large Reservoir is a bit different – it has an enormous high earth bank all around it, so the water level is high above the surrounding ground level (maybe there was gravel extraction there too before the Reservoir was built). A railway runs across the area; it can be crossed at a pedestrian level crossing with a pair of stiles and a lot of looking both ways. To the south of the lakes is an attractive area of thorn scrub with Hawthorn, Dog Rose, Spindle, Bramble and suchlike, with quite a few trees, all very good for wildlife. Down by the lake edges and the Colne Brook are many large Willows and Poplars which grow quickly, lean over, fall, and sprout up anew, forming a constantly-changing cycle of growth and regeneration, and providing cover and roosting-sites for warblers and water-birds.

The lakes have variously been repurposed – one is used by the sailing club, though I more often hear the clatter of rigging vibrating against sail-less masts on windy days than people actually sailing. Another is a strictly private fishing lake, protected by fierce signs and fiercer fences which must have cost a fortune to put up. The lake by the start of the walk is open to wildlife and fishing is forbidden; a delightful trio of icons make it clear that running with a large carp under your arm is forbidden, as is spear-fishing (or is that a black line crossing out a standing fisherman diagonally); frying fish on a griddle is not allowed, though nothing is said about making fish stew in a saucepan, interpret the icon how you will.

South of the scrubland is a pleasantly scruffy pony-field with scattered thorn-bushes and rough grass dotted with tufts of Alfalfa. It rises to a low hill which was once a municipal landfill dump. For some years the dump was grassed over and the ponies roamed all over it; then men came and installed deep pipes to sample and carry away the presumably polluted groundwater; finally, a sizeable array of solar panels was installed and fenced off, complete with security cameras, so ponies and walkers had to make a detour around the array.

So — airport, motorway, gravel-pits, railway, landfill, post-industrial leisure activities, it’s pretty much the classic Urban or Peri-Urban nature area.

The bridge over the Colne Brook offers a glimpse of calm nature; the water babbles softly among the waterweeds, and two Kingfishers dark on triangular wings just above the surface. One swerves into a U-turn, catching the sun to reveal its brilliant blue-and-turquoise plumage. What a moment to start a walk.

We dive gratefully down the few steps from the pavement to the path: the pavement by the bridge is half-occluded by unclipped bushes, and the traffic whizzes past perilously close to unwary walkers.

In the sudden quiet we peer through the trees to the lake. A gang of twenty Cormorants is on the water, with a group of Mute Swans.

The path is bordered with Willows and coarse herbs; a patch of colourful Comfrey, once used to help knit broken bones, attracts some Common Blue Damselflies. At a gap in the Willows, a Cetti’s Warbler sings its abrupt, loud song. Some Migrant Hawker Dragonflies scoot too and fro beside the water, their transparent wings whirring, their long slender bodies glittering blue.

We come to a patch of reeds where we can see right across the lake. A Chiffchaff flits between bushes. On the far side is a bank of Willows, several with protruding dead branches. Perched on these are a few Grey Herons, half-a-dozen Cormorants, and most excitingly three Little Egrets — small white herons with black legs and yellow feet: uncommon visitors here. All of these are predators, feeding on fish and small animals like frogs; the Cormorants fish by diving from the surface, while the herons stand by or in the water, looking out for prey.

The track through the thorny scrub is bright with Rose and Hawthorn fruits — “Hips and Haws” in the fine old country phrase, rich with double entendre, glowing in different shades of red. Across a wide patch of Teasels and Burdocks and Thistles, all tall and prickly in their differing ways, more Hawthorn bushes are still in green leaf but bursting with red fruits, so they are red and green at once, which you might have thought impossible, but there it is, spectacular.

We swing through the kissing-gate and into the pony-field. The animals barely glance at us, the rich grass is clearly far more interesting. “Alfalfa” apparently means “King of Herbs” in Arabic; it was supposedly the finest pasture for grazing animals from goats to camels.

The path rounds the Solar Array; I guess it’s good to know that more and more of our energy is renewable, even if an Electric Vehicle, with its large price-tag, doubtful driving range, and complicated charging arrangements if like me and many city-dwellers, you don’t have a front drive to park and charge it on, is still perhaps a bridge too far. It does feel as if, with one more push, there could be charging points everywhere and affordable prices, and suddenly it’ll look not exotic but obvious. Five years, maybe? Who knows, but at least it’s coming.

A bright, breezy, and much cooler day (16 C, not 29 any more) was just perfect for a visit to Thursley. Perhaps many of the dragonflies decided not to fly: I saw one Common Darter and (I think) one Brown Hawker, and nothing else, so anyone who went along hoping to see the Hobbies hawking for dragonflies by the dozen will have had a wasted trip (and indeed I saw several extravagantly camouflaged types with gigantic telescopes standing about looking very bored).

But everything else was in full swing. A Cuckoo called from the pinewoods. A Curlew gave its marvellously wild, bubbling call from the open marsh. A Dartford Warbler gave me the best view ever of its rufous belly and long tail, as it sat low in a scrubby Birch, giving its rasping anxiety call repeatedly. I enjoyed the view through binoculars. By the time I remembered to take a photo it was half-hidden again.

A Stonechat gave its scratchy call from a small Birch, then hopped up to some Pine trees (so, a distant shot).

A few Chiffchaffs called from the woods; plenty of Whitethroats sang from the regenerating Birches that are encroaching on to the heath. A Green Woodpecker gave its fine laughing call.

So I heard three warblers today to add to the four yesterday, so seven singing warblers in 24 hours, a little bit special.

The lichen flora on the heath was quite beautiful, with Usnea beard lichen, leafy Parmelia, bristly Ramalina (all on old Heather), and elegant Cladonia potscourer, cup, and stalk lichens (three species).

A Linnet sang from the top of a Birch. Goldfinches twittered and flitted about.

And on the path out, a Hobby leapt from a tree right in front of me, where it had been sitting watching the bog pools, waiting for dragonflies to come out and display themselves. It flew round and up, then circled, soaring, away to the south. Perhaps it was the one the twitchers had been waiting to see flying all morning.

Well, after all those sunny late autumn days – it seemed to go on all through October and November, and even in Mid-December it was still as much as 15 C, extraordinarily warm – it is time to get back to talking about conservation work.

Volunteers, a corporate group, and trainees took turns to coppice and dig out the mud in the “Mangrove Swamp” (Willow carr). The newly-qualified chainsaw specialists managed to lay two willows, carefully avoiding felling them completely, to add to the artful tangle of almost-mangrove trunks over the newly-deepened water, thus giving a surprisingly “natural” look after a great deal of work.

We then dragged the cut willow to the edge of the new Birch nursery area. Several Birches have already fallen (you can see a large trunk in the photo), and many others are on their last legs, covered in ivy and only waiting for a winter storm to bring them down. So we have cleared a sizeable patch of bramble to allow seedlings to grow, and protected the area with a woven deadhedge: two lines of sharpened willow stakes (front and back of the hedge), woven with snibbed willow wands, and packed with willow twigs in between. We’ve planted a few saplings we found around the site – an oak, a birch, two hazel – and we hope they’ll be joined by many small birches in due course.

The screech and clatter of the Piccadilly line train filled my ears as we rattled, mercifully quickly, deep below the city centre in London’s fastest and loudest tube line, on the way to Manor House.

I emerged into the grey urban jungle of the Seven Sisters Road, the cars whizzing past the fast food shops as if to escape as soon as they might. Hooded youths hung about the estate gardens in small disconsolate groups. Women scuttled past, heads down, on the grimy pavements. I consulted my map, strode eastwards as purposefully as I could, and crossed into Woodberry Grove.

The gleaming new towers of “Woodberry Down” rose on either hand, the street lined with clean young trees and gleaming black cars. Even the pavements were newly laid in handsome yellow-brown flagstone. It was evidently a shinier, more prosperous Manor that the developers had had in mind.

Around the corner lay the entrance to London Wildlife Trust’s newest reserve, Woodberry Wetlands. It too was carefully landscaped, and money (from Berkeley, Thames Water and the National Lottery) had evidently been lavished on the gateway itself, a cunningly strong rust-coloured hut of iron, the reserve’s name laser-cut right through the metal walls on both sides. The building straddled the New River, a natural moat; and the gatehouse had its own portcullis, in the form of robust iron gates, locked at night.

Huma (of Vole Patrol fame) and two other members of the London Bat Group arrived by car, carrying two enormous Harp traps in big red ski bags. I helped them over the footpath gates, locked to keep people away from bird nesting areas in the breeding season, and they walked around the reserve to a good place under the trees to set up their traps. They are doing some trapping as part of the National Nathusius Project, to learn about that species’ ecology and distribution in Britain.

I walked along the broad new boardwalk to admire the reserve, a ring of reedbed and bushes around Thames Water’s East Reservoir. A Mute Swan dabbled peacefully; a few Mallard and Coot prepared for nightfall. I counted 66 Swifts whirling about the three grey towers across the water.

In an old Water Board building, elegantly converted to a cafe/meeting room, were waiting soft drinks and an excited crowd of the lucky few who’d managed to get tickets for the bat walk.

Huma ran in, a little late, but evidently excited by the result of putting up the traps. She quickly told us a little of the myth and truth about bats – they never get in your hair, they don’t really drink blood (well, vampires do exist, but they’re tiny, and they lap up a few drops of the blood of peccaries (wild pigs), unless humans cut down their forests, remove the peccaries, and then insist on lying with feet poking out of mosquito nets).

She introduced our local bats, too, painting colourful portraits of their respective characters.

We picked up bat boxes, little miracles of electronics with a sensitive ultrasound microphone, speaker, and illuminated setting dial. They work by heterodyning the signal: that is, you guess or choose what frequency you want to listen out at, say 20 kHz (too high for nearly everybody’s hearing), and the device subtracts that from the signal received from the bat, if one is calling. The difference, if you have guessed close to reality, is a low frequency, say 1 kHz, which you can hear. If the bat is calling in bursts (which radar engineers call chirps), you hear those as patterns of clicks.

We went outside and fiddled with the controls. Clouds of gnats, and some nibbling to our ears and cheeks, as well as the whizzing Swifts, proved there was abundant insect food on the wing for any bats that might deign to turn up. Nothing.

Suddenly the air was filled unmistakably with the loud, distant, slow handclaps of a Noctule bat. The Germans fittingly call it the Grosse Abend-segler, the Great Evening-Sailor, as it strides boldly across the dusk sky. We saw no bat, however, just a few Swifts. Presumably the Noctule was far away, its calls detected by our sensitive electronics. We scanned the sky in hope.

And then there was one, plain to the naked eye. And another, and another, and yet more. Five Noctules at least whirled above our heads, uttering loud claps in chorus. With binoculars they looked exactly as you’d think, large batwinged shapes black against the still-glowing sky. Since I was on duty as a helper, I passed the binoculars around; and everyone who looked managed to see what we had come for, bats wheeling joyfully, plentifully, close by, in a London summer sky.

Huma led us on. Between the New River and the reedbed, with bushes and small trees all around, Pipistrelles darted and swerved, buzzed and clicked. They were harder to get in binoculars than their larger cousins, but it was possible. Heterodyned clicks and claps played a chorus all around. Excited fingers stabbed the sky. A Little Egret flapped slowly overhead, on its way to its night roost. The urban jungle felt very far away.

We were called forward in little groups to a gate to see the trapping. Huma came up and showed us a Daubenton’s Bat, her hands gloved against small sharp claws and insectivores’ teeth. The species is a specialist in hunting low over still water: it can scoop up insects from the water surface with a cunningly-designed flap, and if it should fall in, it can swim and take off again safely. The London Bat Group was carefully weighing and measuring the little mammals, and then releasing them. They were using a lure designed to attract Nathusius’ Pipistrelle: it also attracts Daubenton’s, hence the catches. But they did catch a female Nathusius’: Huma was delighted.

Let’s end with a closeup of the main photo. It’s not every day you see a Daubenton’s Bat face to face, let alone in a capital city.

Twitter users can follow the bat study at #LondonBatGroup,

#WildLondon, and #Mostlybats.

An unexpectedly warm and sunny afternoon in May is an opportunity too good to miss, so I went out with bicycle and binoculars along the river, and spent some time in the Leg of Mutton local nature reserve at Barnes. This is a bit of a secret corner, as it’s not far from the WWT’s London Wetland Centre which is certainly far better known. It’s also quite beautiful in springtime, the paths dressed in Queen Anne’s Lace (cow parsley to you) and the lake resplendently blue with new green borders. From the woods, Blackcaps sang all over; from the reeds, both Reed Warbler and Sedge Warbler sang their cheerful repetitive songs: I had a fine view of a Reed Warbler atop the reeds shown in the photo. A Coot with five cootlings scooted about the end of the lake (to the left); a mother Mallard escorted a neat convoy of ducklings; a few Tufted duck preened; five male Pochard dabbled heads-down; more surprisingly, a pair of Gadwall paddled about on the far side. A Mute Swan sat on a nest amongst the reeds. The flowers were visited by masses of small bees. Apart from the planes overhead, the city felt far away.

On the other side of the river (with the help of the handsome green Barnes Bridge) I had a wonderful surprise: House Martins. Four were wheeling and chattering above Chiswick Mall, right by a house decorated with a dozen House Martin nests (many of them visible in the photo), and several in usable condition. This was news to me because the old colony a few hundred yards away was abandoned for whatever reason some years ago. But it is clear that the birds have nested repeatedly in the past few years, and it certainly looks as if they’ll nest again this year. The only small fly in the ointment can be seen on the extreme left of the photo: there is the remains of at least one nest behind some netting, so the birds must have been considered a nuisance on that side of the house, at least. Let us hope that their presence on the front doesn’t trouble anyone, as the colony may well be the only one in Chiswick, and is certainly one of not very many in West London. Being by the river, there are plenty of flies, and the house’s wide eaves with stout supports are ideal for the species.

Winter has definitely set in. The spinach beet in my garden was all frozen, the air at -3 Celsius and the ground presumably rather colder under a clear night sky. Fearing it might all be lost, I picked some and went out to see what there might be today down at Wraysbury Lakes.

Almost the first thing I saw was a bulky little finch high in a waterside willow. It called ‘deu’ quite loudly, fidgeted about and flew before I could focus on it. Still, there was no doubt it was a Bullfinch: the call, its shape, its solitary habits, and its shyness all pointing the same way. It is never an easy bird to see, even where it is resident (it is regularly ringed at Wraysbury). Leafless trees and the rising energy of the coming breeding season provide one of the few opportunities to catch a glimpse of this less well known finch.

At first sight there seemed to be no birds out on the lake. Finding a small illicit patch cleared by a fisherman I set up the telescope and looked about. A Pochard or two; some Tufted Duck and Coot; a male Goldeneye… but the Smew and Goosander of a week or two ago were nowhere to be seen. The old truth is that you never know what you’ll see: but it’s often a delightful surprise, and almost always energizing to be out in nature.

I walked on and looked about again: some rather white ducks caught my eye in the distance. Two male Goldeneye, each with a female in tow. The males threw their heads forward a few times, pretended to preen; one threw his head back and forth, then lowered his head and stretched it out and in. His female swam after him, her head resting on her back as if she were asleep! But she was certainly watching the display, and swimming to keep up a few lengths behind.

A loud squawk betrayed a Heron; it flapped out of cover at the end of the lake and landed on the bank behind the ducks. A few Mallard panicked from the water below me; a Moorhen briefly took flight.

Away from the lake, a few Robin and Dunnock hopped in and out of the bushes. A solitary Fieldfare or two gave their chack-chack call from the hawthorns, watchful and flighty. Another Bullfinch calling, this time atop a bare hawthorn bush – or maybe the same bird, half a mile on – and again I couldn’t get binoculars on to it, despite my stealthiest movements: it had surely seen me at once, and just took a few seconds to decide when to flee.

A Kestrel hovered beyond the tall poplars: no Buzzards or Red Kites today, but really the Kestrel feels almost more special than them, its numbers declining across Britain.

A few Jackdaws, Carrion Crows and Wood Pigeons on the horses’ hill; some Fieldfares in the trees, with a single Redwing; a Stock Dove flying low.