Mirror Shard in Farnham Sculpture Park

Netty found some dusty but very well-made wooden animals, complete with attachment rings, evidently designed for use on a Nature Trail. She repainted all of them and we hung them around the reserve. The camouflaged animals – the newt and the frog – seemed to ‘work’ the best. We hope the children will have fun going around with their parents to find them. One or two may be quite difficult!

It wasn’t all wooden animals. As it happens, we saw some of the real things, November or not.

[Spoiler alert!] We went down to the pond to affix the Dragonfly, and spotted a small limp orange shape floating apparently lifeless at the surface…

Then we started mowing the Ramp Meadow with its remarkably fine stand of Evening Primroses …

… and found a real frog, escaping the scythes and boots.

The Forest School decorated Christmas Candles very gracefully.

Today a brisk southwesterly wind blew the ragged clouds away, and it suddenly felt very much like autumn. The willows have lost many of their leaves, while other trees are still fully clad in green. Down at the Wetland Centre, the Guelder Roses were resplendent in scarlet: the photo is exactly as taken.

Down on the grazing marsh, a few migrant birds were giving the resident birdwatchers a treat. The Peacock Tower echoed to excited calls as a Whinchat perched on a faraway reed to the left, a Jack Snipe bobbed obligingly among some dead reeds to the front, and a Stonechat perched momentarily on a reed to the right. To my own surprise I saw all of them, even confirming that the Jack Snipe was bobbing up and down and had a dark stripe down the centre of its head. When it sat still it was marvellously hard to see, even in a telescope zoomed in and centred on the bird, its disruptive patterning doing an excellent job of breaking up its shape and matching the light and shadow of the vegetation around it.

Round on the wildside of the reserve, a few (Migrant) Hawker dragonflies and some Common Darters were still flying; and overhead, five House Martins, presumably on their way down south from somewhere far to the north, were busy refuelling on the many small insects flying over the water.

Today I gave my ‘Camouflage without Spots’ talk at Gunnersbury Triangle nature reserve. It was very hot, and having helped the RSPB local group set up their stall at the Bedford Park Festival on the common, I cooled off and picked up the materials for the talk.

Helen had set out the tables and baked some amazing Camouflage Cakes – someone joked they couldn’t see them – and we all had lemonade in the heat.

Once I had run through the talk and arranged the talk table with books and materials, I had a quick walk around the reserve. The tadpoles are just at the moment of growing legs – some have none, some two, some four: it’s very beautiful and touching.

A keen entomologist came running, a Clouded Yellow presumably blown in on the warm southerly wind had breezed across the reserve in front of the hut! They are only occasional visitors here, common enough in France, but they hardly ever perch when the weather is warm.

A second entomological excitement: a Pompilid spider-hunting wasp was running rapidly about on some papers in the hut, dragging something white below her body. The photo shows what the naked eye could hardly perceive: she had a paralysed spider as big as herself in her jaws (a leg has broken off). She was presumably running about to find a suitable hole to bury the unlucky spider in, complete with one of her own eggs which will hatch and eat the spider as a supply of fresh, living food, enough to keep it going until it pupates.

A surprisingly large audience congregated for the talk, which looked at tricks that animals use to conceal themselves, often in plain sight. I demonstrated using painted cylinders in the fortunately bright sunlight how countershading works and why it is necessary; and how some animals like skunks and honey badgers use it in reverse to make themselves as conspicuous as possible. We all marvelled together at the wonderful camouflage of the Masked Hunter Bug, the Flat-tail Horned Lizard, and perhaps best of all the Potoo, beloved of Hugh Cott, motionless with its astonishing disruptive markings in the fork of a tree. I risked bringing out my copy of Abbott Thayer’s Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, complete with his fine but sadly misguided paintings of camouflaged Peacock, Roseate Spoonbills and Wood Duck. He was right about the principle of countershading, and the superb disruptive plumage of gamebirds, though.

Then we had more lemonade and ate the camouflaged cakes!

See also the blog article that trailed the talk.

On a grey rainy day, I put on my waterproofs and go down to the Gunnersbury Triangle reserve. A newly-fledged Green Woodpecker flies off. The cow parsley has taken over the whole of the meadow by the approach ramp; last year there really wasn’t very much of it, but now the tall white umbels are quickly turning to seed-heads across the whole area: they need to be pulled up quickly before they ripen. They are accompanied by quite a lot of cleavers (sticky-grass), nettles, hogweed, even hops twining their tall fibrous way over the other plants. And a few brambles are coming up again: we had a blitz a year or two ago, pulling out most of them, and the meadow is much improved, but that hasn’t saved the rather nice garlic mustard (good for orange tip butterflies) from the cow parsley invasion.

I loosen one bunch of roots after another with a fork, and pull up the cow parsley roots – much like carrots, they’re in the same family. When the soil is shaken off they are a pale brown, some straight and carroty, some branched into five smaller swollen roots. When I have a big armful, I carry them down to the dead-hedge.

Digging again, a nettle manages to sting me lightly through the leather-and-cloth gardening gloves. I hear a screaming sound and look up: eleven swifts are wheeling together high overhead, the most I’ve seen over this part of town this year, indeed for many a long while. Sixty or more sometimes gather over the lakes at the London Wetland Centre, pausing to feed before moving on up north on their spring migration.

I gather another armful of cow parsley. The meadow is starting to look a little better. I pull a six-foot stick out of the herbage; half-a-dozen diversely coloured white-lipped land snails, some plain yellow, some striped with black, fall out on to the path. The polymorphism has been argued over by ecologists: it might be camouflage adapted to different backgrounds, some lighter, some darker; or more interestingly, it might be a way of defeating predators like Song Thrushes which could be searching for snails of a particular pattern, so if a bird had learnt that snails were striped and had that ‘search image’, that bird might not spot plain snails, perhaps.

It comes on to rain. I help out in the hut, making preparations for Bug Day when we hope the reserve will be buzzing with excited children and their parents. They will be welcomed by a smiling ‘GunnersBee’, who is a black-and-yellow cutout on a huge blue card with yellow cutout flowers. Even in the drizzle, several species of real bumblebees are busy gathering pollen and nectar.

Well, I usually try to take a pretty picture to start off a posting, but this one certainly doesn’t qualify. These leaf miners grow entirely inside a leaf, in this case of Spinach Beet. As you can see, as they grow they tunnel around below the leaf’s upper epidermis, which is a translucent layer of cells, leaving it intact to provide themselves with a ready-made cover.

Underneath that sheet, a healthy leaf contains a thick green set of palisade cells in one or several layers. These are the leaf’s (and the plant’s) factory, as they are full of chloroplasts, coloured green to absorb light: they synthesize the sugars on which life depends.

Not many people would want to eat this leaf, once the leaf miner larvae – mostly moths – have been at work. The palisade layers are entirely and efficiently destroyed wherever the insects have been. All that remains is an air-space and some dark frass: all, that is, but for the plump whitish cylindrical bodies of the larvae themselves.

Also nesting on the spinach are some ladybirds. These have incomplete metamorphosis, the young being able to walk as well as eat from their first stage or instar. Each time they moult they change in appearance as well as in size. They mainly eat aphids, troublesome pests of many crops, so they are useful to gardeners and to any farmers who don’t want to use insecticides.

This shield bug, seen here in close-up, may look conspicuous enough, but that is the camera’s view. The insect is actually rather well camouflaged, and it generally hides under a leaf where it is in some shadow. The camouflage consists first of a general colour resemblance to its background, with its overall grass-green coloration; and as seen here, it is also disruptively patterned, with the reddish brown of its wings tending to break up its outline. Perhaps it is also somewhat countershaded, with dots stippling its back. Bugs suck plant juices, and their larvae can be quite destructive, but they never seem to do much harm to the spinach.

There are also some green caterpillars, excellently camouflaged with a pale cream stripe all along their sides. (It might be the Hebrew Character moth.) You might expect this to be conspicuous, but it seems to be a classic piece of disruptive coloration: the stripe appears like a sun-glint specular highlight on the shiny crumpled surface of the spinach leaf, rather than part of a solid, round-bodied animal.

A pest I know is there is the Gooseberry Sawfly. There are numerous sawflies in the garden right now, but they are all flying around the Nasturtiums, nowhere near the gooseberry bush. However… plenty of the lower leaves of the gooseberry are badly damaged by sawfly larvae, some eaten right down to the petiole, pathetic little stumps with a few short branching veins all that remains of once green foliage. What to do about it? This isn’t a how-to-garden site, but inspect your gooseberry bush(es) regularly, looking especially at the lower leaves to see if they’re being eaten. If some are, check the edges for caterpillars. If you find any, spray the bush after sunset on a dry still evening (to avoid killing the bees that are pollinating your fruit) with a garden insecticide.

Five minutes of careful searching of half-eaten gooseberry leaves failed to reveal a single larva. The cause in this case is not so much camouflage as the incredibly intense predation by Blue Tits (and Great Tits). I estimate these little birds are a hundred times better at finding caterpillars than I am. They have the advantage of getting in close – they must be able to focus down to a few centimetres, their small eyes acting as short-focus wide-angle lenses – and of being able to perch anywhere in a bush. They also get up very early, and know instinctively exactly what food looks like: small well-camouflaged caterpillars on the undersides and edges of leaves.

Zoologists suppose that birds have a ‘search image’ of the prey they are hunting: perhaps this is much the same idea as the training images that computer scientists use to teach their neural nets to recognise patterns such as faces. Once you have such an image in your brain, you almost instantly recognise your target when it appears. To give a small illustration, I remember when I had a small motorbike, I always saw bike shops everywhere; now I never notice them. My eye was attuned, like a Blue Tit’s to a caterpillar.

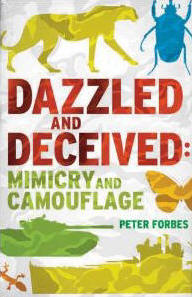

The effect of natural selection on how animals look has attracted the

attention of naturalists from the birth of modern natural history, starting even before Darwin’s Origin of Species.

Visual appearance can affect an animal’s survival in numerous ways.

Camouflage makes it hard for predators to find a prey animal; warning coloration advertises that a potential prey is poisonous or distasteful; Batesian mimicry allows an edible species to pretend to be distasteful; and Müllerian mimicry allows a distasteful species to be sampled less often by young inexperienced predators, by resembling a more common distasteful species. And within these areas, there are infinite possibilities.

But as the cover art suggests, Forbes does not stop there. Camouflage has military uses; and the history of two World Wars reveals extraordinary interactions between naturalists like Hugh Cott (author of the greatest twentieth-century book on camouflage, Adaptive Coloration in Animals, 1940) and Peter Scott with the military – Scott was a naval captain, so he had a foot in both camps.

Much of the book concerns the natural history and biology of butterflies – they include many of nature’s best mimics, and provide incredibly complex examples of visual evolution at work, as the mimic species adapts to each of the many geographic variants of the host or model species. It’s even possible for multiple forms to appear in a single brood. Forbes describes the research workers, their controversies and their heated opinions, right or wrong. Truth wins in the end, but that doesn’t prevent a messy process along the way, just as in evolution.

Today, new light is being shed on the mechanisms of mimicry and coloration in general by evolutionary developmental biology, which Forbes insists on calling “evo devo”. The result of such inquiry will one day be an explanation of the observed, very complex, natural history at multiple levels – genetics, developmental biology, visual appearance, and natural selection, all of which will have to fit together exactly. Pieces of the puzzle are becoming clear, as in the genetic and developmental mechanisms for producing eye-spots. These can be “impressionistic” – they do not have to mimic a cat’s face, as long as a wing-flash gives a bird predator an illusion of eyes-suddenly-jumping-out-at-me; for we suppose that birds have

an escape reaction triggered in some such way. Thus the explanation must take into account ecology too – the behaviours of both predator and prey are needed to explain why eyespots evolved.

Forbes can’t resist putting an artistic and literary take on the natural

history and science: Sir Ernst Gombrich the art historian was deeply

fascinated by visual illusion, while novelists like Vladimir Nabokov (a keen naturalist) were intrigued by truth and lies. Sometimes the analogies go rather far from natural history (electronic warfare is a case in point: it may be deception but it certainly isn’t visual). But Forbes is always precise, and invariably entertaining.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

Free Talk: Gunnersbury Triangle, Sunday 8 June 2014 at 2pm

In this short and I hope lively talk, illustrated with models and photographs, I will try to show that camouflage is a lot more than spotty coats.

Animals use many different tricks to hide themselves. Even when there is no cover to hide behind, animals find ingenious ways to make themselves invisible. And if they don’t need to hide, they use the same tricks in reverse to make themselves as obvious as possible.

“Suitable for ages 8 – 80”. Roughly.

OK, you want more technical detail. Hmm. Well, I shall not be talking about military camouflage, though it is (or should be) based on the same principles as in zoology. The title already promises no spots, more or less, so I shall obviously mostly be avoiding what my hero Hugh Cott called disruptive patterns. Yes, you can see that I’ve spent far too much time trying to improve Wikipedia’s coverage of camouflage. If you nose about in there you’ll discover that I’ll have plenty of spotless methods to talk about. To whet your appetite, here’s Hugh Cott’s beautiful drawing of a Potoo, which makes itself as good as invisible by perching, stone-still, atop a broken branch. I’ll leave it up to you to work out how the trick works. Even better, come along to my talk.