The presenters on Radio 4’s PM programme said that we needed an Awesome Nature Walk to lift our spirits during this renewed Covid Lockdown. Happily, we had already planned to go on one, and here it is: an Awesome Nature Walk at Wraysbury Lakes.

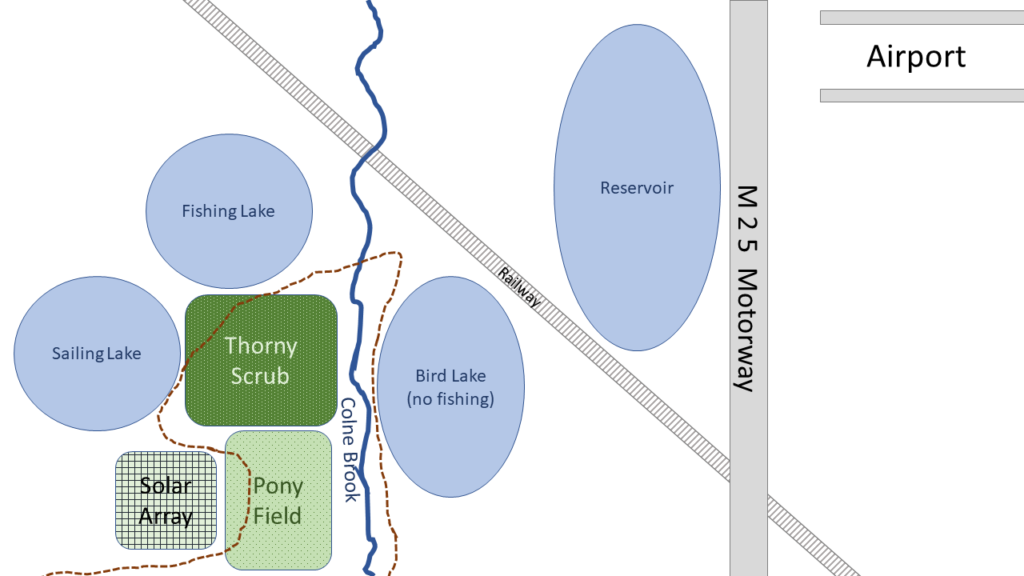

The walk begins near the road bridge over the Colne Brook at the bottom of the map, which is by a repair garage. I’ve drawn the sketch map to give something of the feeling of the route while I’m walking it, rather than attempting to make an objective map.

The area is just outside the M25 ring motorway that informally defines London’s boundary; Heathrow Airport is just inside that, so in normal times (hmm) there is a plane overhead every 90 seconds. Down on the ground, there are numerous lakes which all started life as gravel pits. The River Thames laid down great amounts of sand and gravel in its wide flood plain during the Pleistocene, and the various Flood Gravels now form valuable building materials. Extraction round here has finished, but there are active pits a bit further afield. The pits go below the water table so they fill up by themselves. The large Reservoir is a bit different – it has an enormous high earth bank all around it, so the water level is high above the surrounding ground level (maybe there was gravel extraction there too before the Reservoir was built). A railway runs across the area; it can be crossed at a pedestrian level crossing with a pair of stiles and a lot of looking both ways. To the south of the lakes is an attractive area of thorn scrub with Hawthorn, Dog Rose, Spindle, Bramble and suchlike, with quite a few trees, all very good for wildlife. Down by the lake edges and the Colne Brook are many large Willows and Poplars which grow quickly, lean over, fall, and sprout up anew, forming a constantly-changing cycle of growth and regeneration, and providing cover and roosting-sites for warblers and water-birds.

The lakes have variously been repurposed – one is used by the sailing club, though I more often hear the clatter of rigging vibrating against sail-less masts on windy days than people actually sailing. Another is a strictly private fishing lake, protected by fierce signs and fiercer fences which must have cost a fortune to put up. The lake by the start of the walk is open to wildlife and fishing is forbidden; a delightful trio of icons make it clear that running with a large carp under your arm is forbidden, as is spear-fishing (or is that a black line crossing out a standing fisherman diagonally); frying fish on a griddle is not allowed, though nothing is said about making fish stew in a saucepan, interpret the icon how you will.

South of the scrubland is a pleasantly scruffy pony-field with scattered thorn-bushes and rough grass dotted with tufts of Alfalfa. It rises to a low hill which was once a municipal landfill dump. For some years the dump was grassed over and the ponies roamed all over it; then men came and installed deep pipes to sample and carry away the presumably polluted groundwater; finally, a sizeable array of solar panels was installed and fenced off, complete with security cameras, so ponies and walkers had to make a detour around the array.

So — airport, motorway, gravel-pits, railway, landfill, post-industrial leisure activities, it’s pretty much the classic Urban or Peri-Urban nature area.

The bridge over the Colne Brook offers a glimpse of calm nature; the water babbles softly among the waterweeds, and two Kingfishers dark on triangular wings just above the surface. One swerves into a U-turn, catching the sun to reveal its brilliant blue-and-turquoise plumage. What a moment to start a walk.

We dive gratefully down the few steps from the pavement to the path: the pavement by the bridge is half-occluded by unclipped bushes, and the traffic whizzes past perilously close to unwary walkers.

In the sudden quiet we peer through the trees to the lake. A gang of twenty Cormorants is on the water, with a group of Mute Swans.

The path is bordered with Willows and coarse herbs; a patch of colourful Comfrey, once used to help knit broken bones, attracts some Common Blue Damselflies. At a gap in the Willows, a Cetti’s Warbler sings its abrupt, loud song. Some Migrant Hawker Dragonflies scoot too and fro beside the water, their transparent wings whirring, their long slender bodies glittering blue.

We come to a patch of reeds where we can see right across the lake. A Chiffchaff flits between bushes. On the far side is a bank of Willows, several with protruding dead branches. Perched on these are a few Grey Herons, half-a-dozen Cormorants, and most excitingly three Little Egrets — small white herons with black legs and yellow feet: uncommon visitors here. All of these are predators, feeding on fish and small animals like frogs; the Cormorants fish by diving from the surface, while the herons stand by or in the water, looking out for prey.

The track through the thorny scrub is bright with Rose and Hawthorn fruits — “Hips and Haws” in the fine old country phrase, rich with double entendre, glowing in different shades of red. Across a wide patch of Teasels and Burdocks and Thistles, all tall and prickly in their differing ways, more Hawthorn bushes are still in green leaf but bursting with red fruits, so they are red and green at once, which you might have thought impossible, but there it is, spectacular.

We swing through the kissing-gate and into the pony-field. The animals barely glance at us, the rich grass is clearly far more interesting. “Alfalfa” apparently means “King of Herbs” in Arabic; it was supposedly the finest pasture for grazing animals from goats to camels.

The path rounds the Solar Array; I guess it’s good to know that more and more of our energy is renewable, even if an Electric Vehicle, with its large price-tag, doubtful driving range, and complicated charging arrangements if like me and many city-dwellers, you don’t have a front drive to park and charge it on, is still perhaps a bridge too far. It does feel as if, with one more push, there could be charging points everywhere and affordable prices, and suddenly it’ll look not exotic but obvious. Five years, maybe? Who knows, but at least it’s coming.

Well there are some things one just has to do, even if it means braving the traffic. Nightingales, once common all over the south of England, can now only be heard in a few special places, and Northward Hill is one of them. There are some others in the southeast, like Lodge Hill, and guess what, they want to build houses all over it. Better go and enjoy the birdsong while it lasts.

I was greeted by the song of blackbird, chaffinch, robin, song thrush, and wren as I walked in. A few ‘whites’ – large white, orange tip, green-veined white – skittered about as I reached the attractively rough scrub of hawthorn in full May blossom, blackthorn, wild pear, wild plum, and wild cherry, topped by the occasional whitethroat singing away scratchily.

Into the woods, with a handsome old cherry orchard on the right. Some of the oaks were straight out of Lord of the Rings, splendidly gnarled, knobbly, with massive trunks and holes to hide a good few goblins in.

And yes, sure enough, a nightingale obliged by singing its hesitant but amazingly rich and varied song from the thick cover. A little further, another; and a cuckoo kindly sang its unmistakable song from an oak almost in front of me, then with a ‘gok’ call flew, sparrowhawk-like, from the tree, a special sight.

Down to the hide overlooking the pool in the top photo; I wasn’t expecting more than a coot and maybe a mallard, but there were breeding lapwings chasing off the crows; breeding oystercatchers, and an avocet sitting with them; and a couple of solitary little egrets, stalking and stabbing at small fish or frogs. A redshank gave its wild teuk-teuk-teuk call and flashed its wingbar briefly.

Overhead a few swallows flitted about, and three swifts raced over the marsh.

The Hoo Peninsula is still a wild, spacious, lonely place, even with the swelling villages. You can see the Shard and Canary Wharf in the distance (some 30 miles); the river with its cranes and giant ships is ever-present; but the North Kent Marshes are special, as is Northward Hill with its fine old woods, still unspoilt for birds. Go and see it while you can.

Indian Summer days are delightful, but often not terribly rich in visible wildlife – this year’s young have fledged and left the nest; flowers have faded and gone into fruit (which can be beautiful, of course); butterflies and dragonflies have mostly stopped flying; summer birds have left for Africa; and the warm calm air doesn’t bring winter migrants from the frozen North.

But there was plenty to listen to this morning.

As I walked in off the road, a Heron took off behind the bushes, and gave a two-tone ‘cronk’ note as it flapped off over the lake. I peered through a gap, and there it was, its amazingly broad angled wings like an ingeniously light balsa wood and doped muslin flying machine, totally unlike the awkward folded umbrella of an ungainly bird that a Heron is when perched.

Two Mute Swans took off and flew low over the water right in front of me, as silent as their name: only their wings whistling with each heavy wingbeat.

A solitary Cormorant took off from the water, very black without the white breeding season thigh patches, also silent except for the heavy thwack of its feet slapping the water on the first ten wingbeats.

A Cetti’s Warbler, invisible in the waterside bushes as always, burst into its loud rude song. (Once you’ve read Barnes’s description of just how rude that is, in How to Be a Bad Birdwatcher, you’ll never hear a Cetti’s without smiling again, I promise.)

A Green Woodpecker gave its cheerful triple signature call, somewhere far out of sight. No need to look.

A few Long-Tailed Tits called anxiously to each other, ‘Tsirrup’, high in the willows. I couldn’t see them either, and again, I didn’t mind a bit.

Bizarrely (and this was a sight to behold, perhaps the only one of the walk), 4 Cormorants took to the air, seeming to be chasing 4 young Herons, presumably a family party.

Up on the horses’ hill, a Kestrel hovered silently on whirring wings.

The horses won’t be there much longer: Affinity Water have put up little notices To Whom It May Concern, saying they’ve had enough with ‘flygrazing’ (makes a change from flytipping, presumably) and will remove the horses if they’re not taken away. I suppose the gypsies have left them to breed as well as graze for free (there’s plenty of grass); the horses are always gentle, and do a good job of controlling the meadow, actually. Why would they do that, a friend wondered. I suggested that it made perfect sense – each year, the ‘owners’ could drop in, take a mare, and leave the others to keep up the supply of new horses. What an economical, ecological system. Without the horses, I guess someone will have to pay for mowing, or maybe they’ll hire a flock of sheep for a few weeks each year? Not sure the horses aren’t a better solution. Of course they could leave some goats to go feral. (Only kidding.)