The hut in the Gunnersbury Triangle Nature Reserve, which is managed by London Wildlife Trust, was buzzing with excitement. It was packed full of people on a bitterly cold winter’s day, everyone eager to find out how to map London’s mammals.

You might think that in a metropolis of some ten million people, pretty much everything would be known by now about the city’s wildlife.

But that’s not so. A quick look at the existing maps of some of our mammals – from field vole to otter – tells a simple story. Hardly anything has been published about what lives where in London.

The field is wide open for new discoveries, and those are what we hope to make in the next year as we track down those voles, and maybe some larger animals into the bargain.

London Wildlife Trust has secured £97,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund to study the distribution and abundance of small mammals in 9 woodland sites in West London. Although the focus will be on small woodland mammals, Huma (the mammal expert employed to co-ordinate and deliver the surveys) also hopes that with the help of volunteers she will be able to collect mammal data from a range of sites of different sizes, scattered across the boroughs of Hounslow, Ealing, Hillingdon and Harrow.

On each of the 9 woodland sites, the project will need to find out which species are present, and to estimate their numbers. But small mammals are shy, inconspicuous and mainly active at night. Tracking them down isn’t easy.

So Huma is getting together and training a “Vole Patrol”, a small army of volunteers, keen to get down and dirty with wildlife. That means us! We need to know how to collect data on the mammals, without hurting them, or disturbing them more than absolutely necessary. That means training.

The first thing you might think of is live trapping, and we’ll do some. Huma showed us a Longworth trap, a light aluminium contraption made of two boxes that lock together. You put some food and bedding inside; a trapdoor falls when little feet venture inside.

But small animals particularly shrews need food all the time. You have to visit all your traps after six hours, to ensure that any animals captured are safe, and to identify the species before they are released. We’ll do some trapping later in the year.

We’re starting, instead, with some baited hedgehog tunnels. Hedgehogs are hibernating at this time of year, so we don’t expect them, but the design is proven, and good for a variety of small mammals too. We assemble them from Correx sheets, like cardboard only waterproof. We fold them into a triangular tube, with a fourth side as an overlap, which we stick down with Velcro. Another sheet of plastic slides inside as a tray.

We stick a plastic dish in the middle, and fix masking tape both sides to hold some paint, which we mix up from non-toxic carbon powder and vegetable oil. At either end we pin down a sheet of paper. The dish is baited with special ‘Hog’ biscuits and dried mealworms: it almost looks appetising.

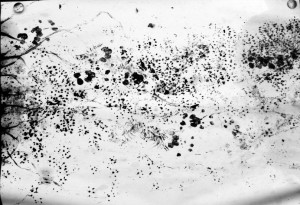

We hide the hedgehog tunnels away from likely disturbance. The next day, sure enough, hundreds of footprints are spattered all over the sheets. The small ones are surely mice or voles; the larger ones not so easy to guess.

As well, there seem to be marks of tails dragged through the paint. We have to repeat the process every day for five days, with each tunnel.

Other volunteers will do the same in each of the other survey sites.

As well as the hedgehog tunnels, we take out a boxful of nest tubes. They’re made of yet more Correx sheet formed into square tubes, each with a simple wooden tray that slides in and out; the back is closed with a square of wood.

These were to be laid out in a rectangular grid. Easier said than done in a tangled, muddy wood! We push through the brambles, trying not to create more paths than we had to, looking for low branches out of sight of the paths, where we could tie on the nest tunnels. Then we recorded their positions with GPS. We’ll go back later in the year to see which of the boxes have been used.

We also put down some plastic tubes baited with mealworms, low down near a pond, for water shrews to visit, and perhaps to leave a few tokens (in other words, shrew poo) to indicate their visit. Species can be broadly identified from their droppings, but Huma is hoping that we might be able to get these, or little tufts of fur, analysed for DNA to prove which species was responsible.

We can find out about mammals in other ways too. Different animals open nuts and cherry stones in their own ways: squirrels snap them roughly in half; mice nibble a neat round hole; voles bite into the shell more irregularly. We found a cherry stone near the first hedgehog tunnel: a small mammal had gnawed an irregular hole with sharp tooth-marks along its edge.

A glimpse of small mammals can be gained with camera traps, as seen on TV nature documentaries. You tie them onto a tree, overlooking a likely mammal run, and with any luck you’ll see mice, or voles, or who knows, maybe a weasel or an otter. London’s mammals are about to become a lot more famous.

Huma is keen to involve as many people from the local community in the project. So, if you would like to volunteer on some mammal surveys, I suggest you contact her by email: hpearce@wildlondon.org.uk