Ravens, several in aerobatic pairs, wheeled overhead, as did a Buzzard and quite a few Red Kites.

A Bullfinch wheezed its odd “Deu” call from a hawthorn bush as we had our picnic.

Ravens, several in aerobatic pairs, wheeled overhead, as did a Buzzard and quite a few Red Kites.

A Bullfinch wheezed its odd “Deu” call from a hawthorn bush as we had our picnic.

The Least Water-Lily, Nuphar pumila, is a rare plant. It’s even harder to find than it could be because it’s small, lives in remote Scottish lochs among other floating-leaved plants (generally way out across a swamp, so impossible to photograph decently), and most famously, because it hardly ever flowers.

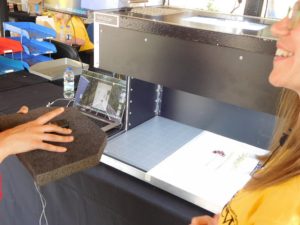

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I learnt about this tantalising little plant while visiting Wakehurst Place, the beautiful country seat of Kew Gardens. That day, it was holding a celebration of its wonderful work conserving seeds of plants from around the world in its extraordinary seed bank, and the staff were all available, full of smiles and sunshine, to greet the public, show off their array of techniques and gadgetry, and to explain their work.

One of the stalls had a display about the Least Water-Lily. It was a small cousin of the Yellow Water-Lily, a common enough plant in quiet waters, but far rarer, known almost entirely from Scotland, barring a probable introduction into Shropshire.

Curious, I looked on the web to see where I might find it in Scotland, where I was about to travel. Lochan Ovie or Uvie was practically the first thing I found, and it was in walking distance of where I’d be staying. A visit, or rather a wild water-lily hunt, was in order.

The lochan was indeed wild, with a wide natural border of wet swampy grassland, and a floating zone with Broad-Leaved Pondweed, Potamogeton natans, and Water Horsetail, Equisetum fluviatile, as stated. White Water-Lilies were reasonably abundant.

But there was no sign of the elusive Least Water-Lily. There was an emergent plant with clusters of three leaves: but these were definitely leaves, not the green sepals of water-lily flowers: and certainly not the rounded, floating lily-pads of the Least Water-Lily.

Some pond-skaters scooted about on the inky-blue water. Some tiny sky-blue insects seemed impossibly to have Marangoni propulsion, motoring about with no sign of legs or wings in the surface film.

A huge boulder, whether from the crag across the road or left over from the Ice Age, was covered in magnificent lichens, one kind a grey-green crust with startling red apothecia.

But I still felt a little disappointed. As I was walking off, I found a Raven’s feather, a bit battered, but far too big to be a Crow’s. A Raven called cheerfully from far above, somewhere up on Creag Ddu.

We had a fine airy walk in brilliant sunshine, cooled by a stiff northerly breeze, around the tip of the Isle of Portland. Underfoot was fine maritime turf and massive Portland limestone, dotted with tufts of pink Thrift and yellow Birdsfoot Trefoil. The sea sparkled blue and silver around a wooden sailing ship with four triangular sails. A pair of Gannets flew effortlessly down the wind, tilting their long black-tipped wings.

To the south, the fearsome tide-race splashed ominously as if some Odyssean sea-monster (Charybdis and its whirlpool?) lurked beneath: the tide there runs faster than a yacht can sail, one way and then the other. Jonathan Raban describes it wonderfully in his book Coasting, the feeling of rising alarm and then, going for it, being shot like a cork from a champagne bottle through the swirling water.

A Rock Pipit, its beak full of insect grubs, called urgently as we strayed too close to its nest. A Razorbill, improbably proportioned like a fat impresario in black tie and tails, flapped by on small rapid triangular wings.

We saw few insects – some bumble bees, some handsome Thick-kneed Flower Beetles glowing iridescent green on buttercups, later on one male perched on a pebble on Chesil Beach

.

The best flower of the day was probably the Yellow Rattle, an odd-shaped parrot-beaked yellow flower with spiky leaves. It’s a member of the Figwort family (like the Eyebright, whose growth habit is similar though smaller), and a hemiparasite of grasses: an important plant, as it weakens the grasses, keeping them low and allowing in a wealth of other flowers. It was once common in our meadows and permanent pastures, but fertilizers and ploughing have destroyed over 95% of these, and Yellow Rattle and the rest of our grassland flowers are now all desperately uncommon.

Overhead, two Peregrine Falcons slid through the air, circling without visible effort. A pair of Ravens came by. Standing at the top of the western cliffs, Fulmars flew out from their cliff nests, circling on stiff wings.

A little patch of Scarlet Pimpernel by a gate again reminded me of how this once common weed of cultivation (and sand dunes – presumably it was pre-adapted to disturbed ground) has declined.

We left Portland and drove down the hill to the Chesil Beach, struck as everyone is by the enormous shingle bar that stretches miles from Abbotsbury to the Isle of Portland, forming a bar with the Fleet lagoon behind it.

A few handsome Sea Kale plants clung to the lower part of the landward side of the shingle, including this one on the edge of the car park. It is the ancestor of the domestic cabbage in all its varieties, from Broccoli to Brussels Sprouts, Kale to Cauliflower. It is itself (obviously) edible, though as a now-scarce maritime plant one wouldn’t want to pick any of it at all often.

Nearby, the ancestor of another valuable food plant, the Sea Beet, origin of Sugar Beet, purple Beetroot, and Spinach Beet. The wild plant too is edible, though the leaves are small, thick, and leathery!

Down in Sussex for a few days, we walked the Seven Sisters from Cuckmere Haven to the Birling Gap.

We had a taste of the scale of human interference with the world’s climate in the shape of a thick haze of pollution trapped by an anticyclone: on the Weald approaching Lewes, we could see the thick haze below the level of the South Downs, and taste the acridity on our tongues. On the coast itself, it was less noticeable in the sea breeze, but the visibility was much reduced with the Newhaven-Dieppe ferry quickly fading into the murk. The BBC warned of high local pollution (worst near Hastings) and an expert advised against strenuous exercise.

The photo of Cuckmere Haven had to be enhanced as it actually looked all washed out in the haze. The geography is interesting: the Cuckmere River emerges (as a dark horizontal line) through what looks from this viewpoint like a continuous shingle bar across the mouth of the valley. The ‘lagoon’ on the landward side of the shingle is part of a former meander of the river, now cut off as if it were an oxbow lake; the current watercourse is canalized with artificial embankments. In the background are vertical sea-cliffs of chalk, with softer (brown) sands above, eroding at a shallower angle. At the base of the cliffs is a white line of fallen chalk rubble, and a dark horizontal surface, a wave-cut platform of chalk (with dark seaweed). In the foreground is the slope of chalk grassland and (left centre) two wartime concrete pillboxes defending the haven.

Gingerly approaching the cliff edge at a crawl, I took this photo, showing a large cave in the chalk: the waves fracture and undercut the cliff at high tide, causing progressive and often sudden cliff falls. The coastline recedes by about 70cm per year, but this bland average conceals a very different reality: the cliff edge barely changes from one year to another, until in some specially violent winter storm, perhaps three to five metres of chalk grassland and hundreds of thousands of tons of chalk suddenly collapse all at once into a gigantic white heap on the beach. The cave in the photo has created an overhang of more than 10 metres; it will certainly collapse one day in the next few years.

The walk was constantly accompanied by the song-flights of Skylarks, and their darting duels low over the grass. A few Ravens flew about the cliffs, and many Jackdaws; a pair of Carrion Crows mobbed a Raven; a few Magpies brought the number of members of the Crow tribe up to four. Near Birling, Chiffchaffs crept about an orchard, and Blackcaps dived into gorse bushes. Hundreds of Brent Geese flew Eastwards in V-shaped skeins or long lines half a wingspan above the waves. Four or five Little Egrets darted about the Cuckmere Haven lagoon, spearing small fish: a century ago they were hunted to local extinction for their plumes, used for elegant ladies’ hats. The RSPB was founded partly as the “Fin, Fur and Feather League”, a women’s campaign against the cruel and pointless use of animals in fashion that became a major force in bird conservation. In the last thirty years or so they have quietly returned to the south coast and are increasing in numbers.