Macfarlane knew Roger Deakin (see my review of Wildwood), and was inspired by meeting him and visiting his extraordinary house. As a young, tree-climbing academic in the distinctly tame countryside of Cambridge, just sitting in the top of his favourite tree outside the city simply wasn’t enough to satisfy his craving for wildness.

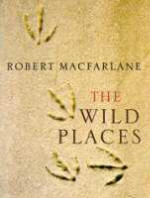

So, for The Wild Places, Macfarlane sets out to the farthest shores of the British Isles, trying both to redraw his map of these islands – not with roads and cities, but coasts and mountains and woods and bogs, linked by ancient footpaths and holloways (roads worn down into the land by centuries of feet and cartwheels), and to define for himself what wildness really means.

In the space of fifteen carefully-crafted chapters, with titles like

Beechwood, Moor, Grave, Holloway and Saltmarsh, Macfarlane introduces us to some of his favourite places, views, treasures – in the form of found stones and shells and bits of wood, in a Deakinesque manner.

Where Jay Griffiths (see my review of Wild) is passionate, even overheated, and Deakin is calm but subtly warm, fiercely rooted in wood, Macfarlane can seem at first rather cold and intellectual: skilful with words, but oddly bloodless. It takes some chapters to start to realize the quality of The Wild Places; a desire to immerse oneself in wildness (both Deakin and Macfarlane favour swimming the wild way, Deakin notably traversing many of our wilder rivers

in his book Waterlog).

There is a plan to the book: around the British Isles, upside down; around the different kinds of wild place – high, low, wet, dry, hard, soft, empty, populated. The last is plainly a surprise to Macfarlane, who travels from an initial rather romantic conception of the places unaffected by man (as if), to places with strong energies of their own, and the people who naturally go with them. There is a bit of dialectic about all this – a thousand student essays on Man vs Nature, perhaps – but it becomes clear that Macfarlane is coming down to earth, and warmth creeps into his writing.

Macfarlane is at his best describing the wonderful diversity of life in the Burren: a rainforest in miniature, in the deep narrow grykes between the clints, the hard, dry exposed slabs of limestone pavement: an endangered habitat if ever there was one. And his love for Coruisk, beyond The Bad Step in the Cuillin Hills of the Isle of Skye, shines out despite any clever word-schemes or devices.

Buy it from Amazon.com (commission paid)

Buy it from Amazon.co.uk (commission paid)

See also Macfarlane’s The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot