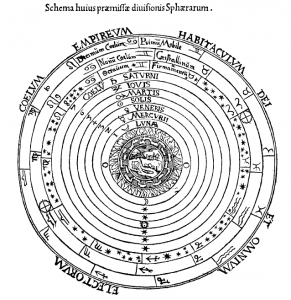

In the Middle Ages, nature – understood as the world of change and decay – stopped at the orbit of the moon; all else above the moon lay in the orbits of the crystalline spheres, culminating in the Empyrean Heavens, the Dwelling Place of God and All the Elect: definitely not ‘nature’ then. The revolution in cosmology and physics brought about by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton swept all that away, so today I can happily talk about events in the heavens as natural.

It was spectacular. At 9pm, cloudless night sky was dominated by a brilliant full moon in the southeast, with a brilliant planet – brightly orangey-red in binoculars – just above it. The pundits say the Moon and Mars were just 3 degrees 19 minutes apart. With Mars about as close to Earth as it ever gets, and the moon almost dazzling in the binoculars (it would have been painful through the telescope), it was a fine sight. The ‘planets’ (as they would have said in the Middle Ages) were in the constellation of Virgo, but the moon’s brightness made the background of stars all but impossible to see.

The orbit of Mars is outside the Earth’s, so the planet can appear anywhere around the sky on the ecliptic. The two orbits are both nearly circular, but the planets rotate around the sun at different speeds, so it isn’t often for the two to be close to each other as they are at the moment. And it’s more interesting visually when the Moon is full, its whole disk lit up by the Sun, which means it is opposite the Sun. In other words then, the Sun, Earth, Moon, and Mars are all nearly in a straight line to bring Mars close to Earth, and the Moon to the full position. It doesn’t happen every day.